Place: Baruch College, CUNY

17 Lexington Avenue (E. 23h Street),

Room A306 – Skylight Room, Manhattan

Date: Friday, March 19, 2004 Time: 8:30AM to 4:00PM

Parmatma Saran: At this point I would like to invite the members of the panel to come forward. [inaudible] I have the honor to introduce the presider of this panel, Professor Meena Alexander. I have the privilege of introducing the previous presider, one of our distinct professors at CUNY. Meena is our second distinguished professor here of English and Women’s studies at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY. Her poems and prose works have been widely anthologized and translated into several languages including Arabic, Malayalam, Hindi, Japanese, Italian, French, German, and Swedish. Her works include the memoir Fault Lines, selected by Publishers Weekly as one of the best books of that year; a volume of poems and prose pieces on the immigrant life. I could sit here, I could go on and on, but a distinguished professor [inaudible] doesn’t need any more introduction.

Meena Alexander: Thank you very much for that most gracious introduction; I hardly know what to say. I would like to start by saying I am so very pleased to be here at Baruch College. This is my very first time at Baruch. I have been at CUNY for many years, but this is the first time I’ve had a chance to enter Baruch College. And particularly I think to be chairing such a magnificent panel. We have quite a treat in store for us today because we have a series of presentations that range quite widely around issues of women’s survival and creativity, and I think in that order, because I think that issues of creativity also involve survival, a fight for survival. And I think all of the presentations are different ways they involve issues of diaspora, and of making a home, whether it be through literature, or the [inaudible] activism, or through the creation of fine art.

Meena Alexander: Thank you very much for that most gracious introduction; I hardly know what to say. I would like to start by saying I am so very pleased to be here at Baruch College. This is my very first time at Baruch. I have been at CUNY for many years, but this is the first time I’ve had a chance to enter Baruch College. And particularly I think to be chairing such a magnificent panel. We have quite a treat in store for us today because we have a series of presentations that range quite widely around issues of women’s survival and creativity, and I think in that order, because I think that issues of creativity also involve survival, a fight for survival. And I think all of the presentations are different ways they involve issues of diaspora, and of making a home, whether it be through literature, or the [inaudible] activism, or through the creation of fine art.

So I will just briefly introduce each of the presenters in the order in which they will present. And I just wanted to say that if there is anything I have left out, please feel free to introduce yourselves as well.

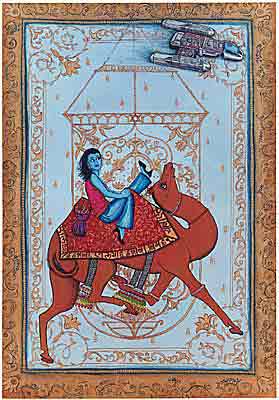

So we will start with Siona Benjamin who is a painter originally from Bombay, now living in the U.S. Her work reflects her background of being brought up Jewish in a predominantly Hindu and Muslim India. And so you already you have multiculturalism of India entering her work. In her paintings, she combines the imagery of her past with the role she plays in America, making a mosaic inspired by both Indian miniature paintings and Sephardic icons. She has an MFA in painting and another MFA in theater. She is exhibited widely at numerous galleries and exhibitions. She is the recipient of a 2004 fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts.

We will then have Jaskiran Mathur who is with SAKHI for South Asian women which is an extremely important women’s advocacy group here in New York, and indeed an important group in the United States. I am going to read, if that’s alright, your bio from here, because [inaudible]. She is a sociologist from India, with a background in gender issues, rehabilitation, development, and volunteer work with rural and urban women in India and the U.S. She has been in the U.S. since 1998, and has worked with the World Bank and UNESCO, and has taught also at Teachers College, and is currently teaching at [inaudible] College.

And our last but not least in our order of presentations is Sunita Peacock who is going to be talking about literature, South Asian literature. And she is an assistant Professor of English at Slippery Rock University in Pennsylvania. She teaches classes such as Eastern and World Literature [inaudible]. She graduated with her Ph.D. from Southern Illinois University. Her major there was Modern British Literature and her minor fields were Women’s Studies and Postcolonial Theory. [inaudible] are of interest [inaudible].

Siona Benjamin’s topic is called, “Finding Home and the Dilemma of Belonging”; Jaskiran Mathur’s topic is, “Empowerment—the SAKHI Experience”, directly [inaudible]; and Sunita Peacock’s topic is “The Negotiation of Space: Interrogating identity in the lives of South Asian/Indians.” I would like to request that speakers speak for about 15 minutes, not more, not more than twenty, so that we have a chance for discussion at the end. Thank you very much. So please welcome our first speaker.

Siona Benjamin: [*author unwilling to send text or images, but sent me website for some of the paintings she discusses. http://www.cherylpelavin.com/artists/benjamin.html

Question of copyright for publishing images? cf]

Thanks very much.

I am going to show slides, and I hope you can see the visuals. I did not anticipate the skylight.

In the mythology of India, a yogi is a female ascetic and looks like, in the book Davie the Great Goddess, by [??? V Roger], [[inaudible] of which an attendant of the god [inaudible]. Yogis, like their male counterparts, renounce society’s norms to seek spiritual knowledge, magical powers, or immortality through the practice of yoga. Through yoga the yogani strives to achieve suhatee, a state in which the practitioner of yoga transcends duality by recognizing the self as universal [one]. These supernatural powers range from extraordinary wisdom to the ability to fly to enter the body of beautiful women and animals to arrive at the dead and foretell the future. The yogis desperate longing for enlightenment, the yogani has to suffer extreme austerities in an effort to achieve spiritual bliss.

The yogi in my paintings are in search of similar powers. In today’s world, much is needed to be done to counteract the effects of war and its horror and to cease the death of Judaism. As I sat in my studio one morning contemplating my previous night’s work, I felt both a great strength and power in being an artist. AT the same time, I felt a great sense of helplessness. What could my art possibly contribute that might help?

The yoganis in my paintings were painted shortly after. Because I think both the powers and the aspirations of the [inaudible] aesthetic. In Finding Home #41, a self-portrait in which I am holding a fly swatter and standing on a hill and wearing my bathrobe which suggests domesticity, I am able to do absolutely nothing about the two hands that appear below and aim guns at each other. It is during mundane activities of life that profound realizations make [inaudible].

In the second of the yogani paintings, #42, I brush my teeth and water flows uncontrollably from a tap at my feet. I hold a mirror up to the viewer asking if he or she is the culprit, the cause, the wrongdoer, the instigator, the demon.

In Finding Home #43, like the yoganis of before, I lay on a bed of nails in penance while my bathrobe drips blood. My daughter, in the garden of the angels of Persian miniature, brings in the Hebrew letter aleph on a golden platter, perhaps suggesting the return of the beginning and hope. The bathrobe repeats every time reading the Shamash, a Hebrew prayer taught to me in my childhood [inaudible], sometimes dripping blood, sometimes becoming a fearsome flame.

In Finding Home #44, I incarnate myself into a [inaudible] like woman. With my robe flaming behind me, I overcome a nuclear weapon by crushing it underfoot, its black, oily blood oozing. Hope never really left as I hold it like a small yellow flame against my breast.

In this series of paintings entitled, Finding Home, I raise questions about what and where is home, while evoking issues of identity, immigration, motherhood, and the role of art in social change. I am a Ben Israel Jew from India. My family gradually dispersed, mostly to America and to Israel, but my parents remained in India. I am now an American living and working in New Jersey, and am married to a Polish-Russian man from Connecticut. With such a background, the desire to find home, spiritually and literally, has always preoccupied me. The feeling I have of never being able to set deep roots no matter where I am is unnerving, but on the other hand there is something seductive about the spiritual borderlands in which I seem to find myself.

The next few slides I will show you will show you a couple of slides [inaudible] Jewish India, to give you an idea. This is a map that I found in the New York Public Library that talks about the different ways the Jews came to India along with other all the groups, the Greeks and Portuguese and everybody else. [inaudible] time, I’ll show you.

This slide shows a synagogue. I grew up in Bombay in the city of Bombay. The [inaudible] synagogue. This is a famous Cochin synagogue built in the 15th century in south India. This is one of the many synagogues in India, just to give you an idea.

This is actually [inaudible], they are prayer scrolls which are contained in decorative containers. The one to your right is from India, and the one to your left is from Iran.

Recently I have been studying the Torah, the five books of Moses and the Talmud, rabbinical [inaudible] to the rabbi in my [inaudible]. While growing up in India I recall being surrounded by idols and iconography that were taboo in my Jewish world. I eyed these figures from a distance, captivated with their radiance and richness. Since Judaism stressed monotheism and iconoclasm, I finally understood the layer of figurative drawing for years. Initially making abstract work, and then later as I did eventually depict the forbidden fruit, my figures were shrouded in darkened faces.

This is some of my earlier work.

Now my work is filled with graven images. I suddenly have become clear in my years of studying and designing sets for theater, that I like the narrative, the theatrical, the decorative line. This ornateness I carry with me all around. These figures have thus become characters in my paintings that act out their parts, restoring, balancing, rectifying,

recording, and [inaudible] . Some of my idols are painters like [inaudible] and [inaudible Barro] who are surrealist artists. [inaudible]

It is through all of this that I understand how I listen to my own personal [inaudible] and universalize. That’s playing the role of an artist activist.

This one is called Venus. I did this after the last presidential elections. Venus being a symbol of western sculpture from studying western art. But in this case she is counting chad, she’s picking up a ballot card, holding up her own tattered halo, a crystal ball of course to look into the future, and she’s picking up her own dress to reveal a bloody army boot. So kind of taking symbols form both western and eastern mythology and art and kind of working with that.

In the series title Spicy Girl I address modern American culture in the context of my own background, having lived in these two diverse cultural settings. Spicy Girl projects an in your face attitude to American culture but also toward the stereotype of Asian women. The first one is called “All Around Techniques of extacy.” These are [inaudible] multimedia in the spirit of making toys, that I do in between the more serious Indian miniature paintings. [inaudible]

The second one is called Spicy Girl – Don’t Get her Started. It is actually found object boxes [inaudible] about the red dot. How many times have I been asked, “are you born with that dot?” And I got tired of shaking an angry fist at them and saying “how come you don’t know” so I decided to handle it with humor. That [inaudible] is the outside view and this is the inside of the box when you open it up.

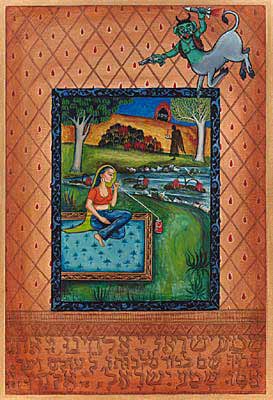

In Finding Home, #28, inspired by this Indian miniature painting of a court scene with a woman smoking a hookah with her courtesans around her.

In my painting 28, a figure of myself in blue jeans seated in a traditional miniature landscape sipping Coke through a long straw that suggests a hookah. I am imbibing the intoxicating American elixir/poison Coca Cola symbolizing the lure of the west that draws me into the U.S.

In the background, the house mother imam in Hebrew and representing the home I was leaving in immigrating to the U.S, the once lush foliage the blooming lotuses in the pond are now wilted and the water is filled with trash and pollution. There is a demon on the top of the painting with a gun and nuclear weapons that suggesting war will infiltrate and [inaudible]. However a protected Asia is also in the background with my mother’s [inaudible] and the entire scene is set within the protective border of the central Hebrew prayer, ensuring that my Jewish spiritual identity, will accompany me into my new home.

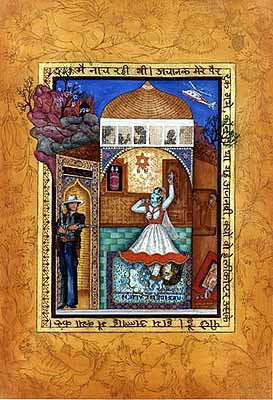

This one is inspired by Bollywood movies. Actually I grew up in Bombay, in Bardra [sp??] and my mother ran a Montessori school for 20 years, and [inaudible] came to my mother’s school and it was quite a scene around my house when he came to drop the kids off. This one is called Finding Home, #49: Dorena’s encounters with Mr. Eastwood.

But who is in whose space? Is he in hers or vice versa? The resident alien card which I recently gave up to acquire my American citizenship is disguised under a Persian carpet.

Around the painting it says in Hindi, “I was dancing.” Suddenly my feet stop. Who is that stranger? Why is a helicopter after him? Oh, I laugh, what should I do?

In Finding Home #31, around the painting of the water I have written, “It was a quiet day in the desert, I almost fell off my camel. I knew that I reached America when I saw a starfighter spaceship fly by.”

In Finding Home #45: I have a sister, is done in response to the Middle East crisis. Since most of my family immigrated to Israel from India, thus I formed this two-headed, several-armed woman, half Jewish, and half Muslim. Both her hands [inaudible] In front of them is a black plunger and wires that suggest a bomb connected to them. Will they destroy themselves, or is there any hope that they will be safe from themselves.

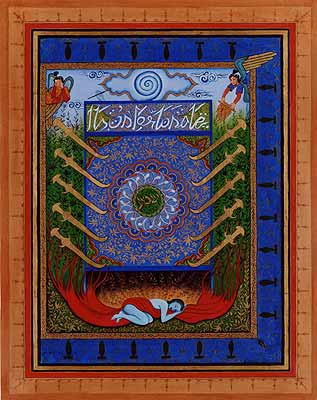

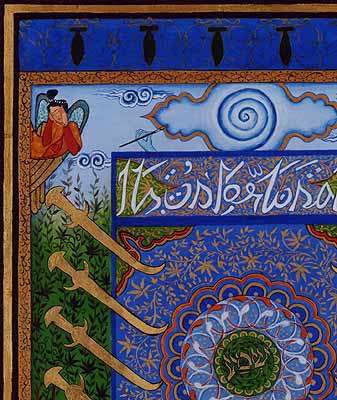

In Finding Home #56, entitled [inaudible] which means [inaudible] in Urdu is inspired from the pages of the Koran but also from Jewish illuminated manuscripts. Are the swords weapons that will defend her or are they a protection against unforeseen danger? What seems like Urdu or Arabic writing across actually spells out “the unfortunate” in English.

This is a detail at the bottom of the painting.

In Finding Home #61 titled “Beloved”. Unable to deal with the conflict between Sarah and her god, Abraham tells Sarah to do what she is right in her eyes. Although Abraham has been instructed by god to listen to Sarah’s wishes, the version taught to me in my Jewish Torah, he seems not to care that Ishmael’s son is banished into the wilderness by the mother Hagar. This competition between the two mothers results in a rift between them, since they are safeguards the right of personal idols [?inaudible]. Sarah and Hagar in my painting, titled “Beloved”, are reunited. In this embrace, they are mere reflections of each other. Being raised Jewish in a Hindu-Muslim India, I grew up having close friendships with Muslims. I cannot but see the similarities we share as human beings, not differences. But danger lurks. Out of the shadow comes offering a friendly extended hand. Strapped to his chest are bombs that will explode, only if he can draw the attention of Sarah and Hagar. The amputated soldier cannot save them can he? The camera has spotted the suicide bomber, but will he be stopped in time, and the fragments of Sarah and Hagar’s bodies put back together again? [inaudible] somebody else [inaudible].

In Finding Home #64 titled “Hagar,” Hagar and her son Ishmael leave home and embark on a personal [inaudible] which means in Hebrew “going forth in the desert.” Dying of thirst, she encounters water and quenches her and her son’s thirst. Water is often a symbol of spiritual belief and strength in the Torah. She encounters water and thus her spiritual belief is rekindled. The Hagar in my painting encounters water and is surrounded by it. She walks and floats on it. Her Moses-style staff has reduced the nuclear mushroom cloud and contained it under the water, but the water is undrinkable as within it are the fragmented bodies from a suicide bombing. Is she Hindu or Muslim from this India I left behind? Or both? The thread of her fabric unravels, or do they grow to become trees, while her many many homes fly away on the fabric of her sari?

The last two pieces. Finding Home #63, titled, “Ruth”. Ruth the Moabite, as she was originally from Moab, a nation bordering Israel, she refuses to leave her widowed mother in law Naomi. Being a young widow herself, she says to Naomi, “your people are my people, and your blood my blood.” Like Abraham, she is also performing [inaudible], by coming into the new land of Israel and leaving her own homeland. The character Ruth strikes me as faithful, benevolent, and altruistic. By learning about these various characters in the Torah, I found that studying them was like analyzing characters from a Shakespeare play After learning as much as I could about the roles they play, I wished to make my interpretation or [midrush]. Instead of painting them in their time and aesthetic, I wished to bring them forward to our time and have them combat today’s people, war, nuclear weapons, and [inaudible]. How would Ruth react? How would she contain or destroy the injustice of today? I would like to think, given her benevolence, she would ingest the weapon. She would swallow the dagger that threatens to destroy, and with this effort, she would hope to arrest the mushroom cloud, even before it envelopes the world in darkness.

Finding Home #60, “My magic carpet”. “Someday Palestine” I grew up hearing my grandmother say, and she did emigrate to Israel eventually. Did the magic carpet [transport] the promised land, or did it dislocate it? Her one hand transformer into a paint brush. Is it paint or blood that flows wasted into the drain? Two of her many hands are shackled, but does she know that she holds the key? She balances a bowl that collects golden drops, or is it [inaudible]. While one claw-like hand destroys her own painting the two hands above rekindle a flame of hope. I think I have [inaudible] detail. By the way, these are all gouache on paper or gouache and 22-karat gold leaf on paper or gouache and 22-karat gold leaf on wood panel.

And one of the last pieces, Finding Home #46, is titled “Tikkun ha-Olam,” which means the reconstruction of the world. It is inspired from a concept in Kabbalah, which is a form of Jewish mysticism. Here the world is compared to a pot or vessel which contains all the virtues; however, the pot is unable to hold this divine energy, and the pot shatters. But the broken shards retain the divine energy, or life. It is humanity’s path to reconstruct this vessel, which is done through various ethical, spiritual, intellectual, and aesthetic acts which reestablish values in our world. By making images that contribute to this Tikkun or reconstruction I am thus participating in my own small way in this process of restoration or reconstruction. Thank you.

Jaskiran Mathur: I am a sociologist and [inaudible] a college in Brooklyn. My association with SAKHI has been as long as I’m staying here in America. I volunteered at SAKHI and then worked for SAKHI very, very intimately as a domestic violence program coordinator, and have been on the SAKHI board for three years.

So today I am here today about SAKHI and the SAKHI experience. I will give you a bit of a background of SAKHI. Is Meena here? [inaudible] [inaudible] [inaudible] SAKHI has grown a lot in the last 15 years, and made a certain presence in New York city. It is an organization devoted to working for South Asian women. And I am sure in this forum I don’t have to define South Asian, which is something we usually have to do when we start talking about SAKHI in our outreach work. Established in 1989, this year we proudly celebrate 15 years of survival and [inaudible], as we say. SAKHI has grown to be an organization which now handles much more than we ever expected to, and we have always said this is an organization with a death wish because we live for the day when we will not need to exist. We started off because of our concern for victims of domestic violence. It is inevitable when you take up one particular issue which is problematic in society, your attention is instantly drawn to other issues connected to that issue.

So our main program was domestic violence and how to respond to it, but it was humbling because responding to it was all we were talking about at that point. And of course we didn’t want to [inaudible], but all we could do was be there for women who were so far away from home, very much like a loose following in the footsteps of spouses, families, and [inaudible] these women and then finding them in the system, finding them in a problematic situation, and SAKHI means, in most South Asian languages, but female friends. And we tried to be friends. To provide an ear for these women.

This humble beginning of being an organization where we could find [inaudible] familiar with the culture and maybe with languages and found direction, quickly grew to include an effort towards community outreach, and also to build a dam. Because there is no point in having an organization which is not meant to [inaudible], there is no point in having an organization which is not there to be consulted, that this is a problem within the community and we have to acknowledge it. And let me show you that that has not been a quick process, the technology has come really slow, but it has come gradually, and of course to be able to be a source for people who require help and to provide them with that help and information and guidance. To raise awareness amongst the women who come to us for help, and to raise awareness within the South Asian community that domestic violence is a problem which we don’t like but which exists in our community. It has been an important job, so that is how the second task, the general job of SAKHI is seen: community outreach, and awareness-raising.

Closely linked to that is our economic-empowerment program which is [inaudible] important program because any effort to help women would be meaningless unless it could be directed to some viable option, to be directed in a direction that they could stand on their own feet and find their own way. Empowerment is what I will focus on as I tell you a bit about the SAKHI background.

Economic empowerment, which began with classes and computer training, is an ongoing process, and we are working hard to build [inaudible] program. And from our realization that violence or abuse is not just a physical or emotional pain, but it has immense repercussions in terms of health, both mental and physical health, and the health of the community. The health initiative at SAKHI has taken up another major program which we are working on and we have gone from these initiatives, which are dealing with issues at the ground level, move also to the idea that we could and should be there wanting to do [policies? inaudible] because you can’t just keep looking back on problems, without trying to stamp things out. I would just like to introduce you to one of our major efforts we are trying to work on policy and that is our co-interpreters program where we have [inaudible] of New York state and New York city co-systems and co-interpretations in South Asian languages, [inaudible]. Justice [inaudible], denied. So that is something we need to focus on as well. That is one thing [inaudible] obtained on the kind of things we have been doing for the last 15 years and may be out of date.

In 2003, we received a total number of 515 people you have the statistics [in the brochure] so I won’t go into details, and these calls are coming from women spread across the south Asian community, so we don’t have any specifically [any] [inaudible]whom we are working with from last year from Sri Lanka, but we do have ongoing work from before that. But India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indo-Caribbean community, Nepal, Burma, Afghanistan, and some non South Asian communities too have been reflected in our statistics and in the whole group that we had. We have also been working in all the boroughs of New York city, and we also have respondents form the tri-state area, as well as from other states, as well as from India and other homelands, and some of the other survivors who have been approaching us.

So given this kind of environment, we seem to be getting very close to our goal of eradicating violence completely or doing away with SAKHI and other organizations we won’t need anymore, but we are trying to make this an organization whose presence is felt and thus performed. I will, the handout which has been distributed has some testimony from people who been helped by SAKHI. If we have the time [inaudible].

Meanwhile I would just like to go to the topic that I have chosen for today’s presentation. And that is the empowerment. Sociologically speaking and talking about developments that I have been interested in and I am going to borrow [inaudible]’s definition of empowerment, and say that empowerment is about social [inaudible] and it is about the people. I am not talking about ordinary people, common people, not people who are conditions of birth or some other socially or culturally advantaged person. Empowerment is therefore a process of building capacity and confidence and taking positions about one’s own life at the individual and collective level. And gaining control over the [inaudible] resources. The empowerment process is facilitated by creating awareness about one’s rights and responsibilities and socio-economic, educational and political opportunities, by developing skills to be utilized by productive people, and by modeling oneself on activities in community life.

Empowerment is about change favors those who previously exercised very little control over their lives. And this an effort which is ongoing in most communities, because there is a realization that these [inaudible] by most governments, by most agencies, there is [inaudible] no way there can be real a social change unless those who are disempowered can be empowered. In the earlier session, we heard a presentation about the micro credit experience in Bangladesh which has become the success story of the Grameen Bank experience, and microcredit groups and other [inaudible] have been sapped in the process of empowerment, or as a partner in empowerment.

The SAKHI experience which can certainly be linked to this. We haven’t created a [cooperative] or selfish group, we are like an entrepreneur, we are an NGO, [inaudibl]e volunteer organization, and we do try and facilitate the process of people becoming aware of their rights and of ways to empower themselves and of ways to solve the problems they have faced. Because these people, for various reasons, social, political, personal, have been denied, even cultural, have been denied access to this kind of information and this kind of knowledge.

The basic understanding of the theory is that there can be no true empowerment or true social change unless the communities in which those who are exploited or those who are resourceless recognizes the role it plays in creating this environment. Why I am bringing up this is issue? Because very often in the SAKHI effort we have come up against a response which is very disturbing. And that is, “But this is a cultural thing. The position of women in our society is the way it is because culturally effect our own behavior in a particular, or our families, our make up of the culture.” This is using culture as a scapegoat. Because culture is constructed, and man-made. It is not something which is a revelation from above. And we have created this culture, and [inaudible] vested interests, [inaudible] contradictions. But to say that this is cultural, they hope it will not interfere with it or have much do with it or pretend that it is something which is restricted to certain groups in certain communities. We had this interesting information about the leather workers, that was in the earlier session, which I found very amusing, because it does makes a lot of sense to say that we don’t kill the cows or pigs, I mean they are dead already from another person, we only work on the level of byproduct of the killing which is for meat or whatever else. You talk about the South Asian experience, actually Indian culture we have class system which actually is institutionalized and [inaudible] function. We have people who are tanners and workers in that tradition who are [inaudible] no body is [even surprised,] it is not like they don’t use the products. But they didn’t have anything to do with unclean people who do unclean jobs, but they were [inaudible] so there is a level of rationalizing and explaining what is happening, what makes sense within it. And there are some vested interests that serve some purposes.

What we have been experiencing is that there is no point in just dealing with people who have been the victims of some of the exploitation society metes out, or have been victims of certain [inaudible] unless we can influence society or bring the level to society that these problems have to be dealt with by society itself. It is not just enough to say policy. We know policies, being from south Asia, within those countries, that there are laws and very progressive [aggressive?] laws. We have laws about . . . in fact if you look at progressive laws, [inaudible] concern that south Asian laws are really so progressive that I was horrified to find that there is hardly any maternity leave in America. [inaudible] When I came to America and I had availed of three months. I was born in India and it was such a great thing, it was such a progressive thing, but I took it for granted when I was there.

So you can institute law, but the traditions and different for a person who is aware of their rights are. Law is what is written in a book, [inaudible]. And if people are not made aware of what they are entitled to, it makes no sense having laws, etc. There has to be a connection made between what people are experiencing, what they know in terms of alleviating their suffering, what the community’s role is in that suffering and alleviating that suffering is, and the community should speak up and say and be responsible for it. So it is only organizations which work with the victim and work with the community and have a knowledge about the culture, to which the communities and the victims belong. It is only such organizations which can help to bridge these gaps. Or can say we belong to the same community we come from the same place. And we think some connections are required or some connections need to be made. This is an effort we are in the process of.

And the SAKHI experience, let me sort of summarize it to you, I will read out to you one or two endorsements we have from people we have helped. I will read out the experience of “Rasheeda” from Lahore [inaudible]. The names are changed but the words are their own. Rasheeda writes, “My fault was that I had a Master’s Degree. When I got married, I was very happy that my husband settled in America and I was joining him in the land of dreams. But soon I realized that he was a very short-tempered man who wanted me to constantly fulfill his wishes and that of his family. I was routinely taunted and told, `You think you are too educated, but that means nothing, because I control you and will do only what I want.’ I was his prisoner—and I thought I would die . . . Then my neighbor told me about SAKHI and accompanied me to the SAKHI office. They helped me in many ways including helping me get back on my feet. With SAKHI’s help I applied for scholarships and now I am studying computer science at my local college. Today I can envision a better future.”

This is a very simple explanation, [inaudible], some help and support [inauduible] which was so far away from her home. I am willing to respond to whatever questions you might have about SAKHI’s when we’re done with our presentation, because [inaudible]. Thank you for listening.

Sunita Peacock: In this paper, I would like to interrogate the identity and space of south Asian immigrants in the U.S. I would like to do this through the fiction work of [inaudible] and theorists such as Homi Bhaba and Gayatry Spivak Chakravorty. And other Indian critics who question the identity of Indian immigrants [and] their writing. I will also examine one article, I have several but I’m just going to look at only one, from news magazines [inaudible] culture, too, to show how Indian immigrants are trying to negotiate a space and identity for themselves in mainstream American society. [inaudible] look at the lives of Indians immigrant in the U.S. to examine the history of immigration of this particular group into the continent.

The influx of immigrants to American began as early as the 1890s, mostly as agricultural workers and laborers in the U.S. and Canada. The next group arrived in the late 60’s, the time period of the Vietnam War when the heated economy created demand for professionals willing to work for low pay especially in the fields of medicine. Later in the 1980’s, immigration began instituting stricter laws and this brought about a different kind of Indian immigrant, one who belonged to a poorer class and accepted jobs as cab drivers, shop vendors, etc. In the 1990s, the U.S. opened doors to Indians throughout the upper echelon of corporate America with the arrival of the dotcom generation. So today we see the Indian population in the U.S. as prosperous, well-educated group, occupying an important niche in the immigrant population in this country. Despite this standard of self-sufficiency the Indian immigrants have attained in the eyes of the dominant western Caucasian society, there are several conflicts, particularly spatial, as it moves in and out of cultural spheres in American society.

So I would like to examine spatial identity of the Indian immigrant and to show how important the notion of space is to the immigrant by looking at some of the fiction of [Mukherjee].

Suffice it to say that when the Indian immigrant arrives from India, he or she comes with both metaphorical and physical baggage. In India specifically, the geographical space of the country has been physically challenged over centuries. This is one subcontinent that has been conquered on numerous occasions by foreign invaders beginning with the Greeks, Alexander the Great, to the Persian and Muslim invaders, to the British, causing diversity in both language and ethnic origin of the Indian people. Before the British reigned supreme in India, it was the [inaudible] Muslim kings who ruled India, and since the Muslim influence was much greater in northern India attempts to impose Hindi, a [northern] language, on the national level, failed in the south leaving English as its lingua franca in India.

Also because of various foreign invasions in India, people are varied in their customs, culture and religion throughout India. Although this calls for diversity, India has been wracked by religious and separatist strife for the most part of modern history.

So Indians arriving in the United States don’t see themselves as South Asians, but more in religious, regional, and linguistic terms. Indians belonging to the older generations also separate themselves into class and caste. So the term South Asian becomes more a political construct.

At any rate, Indians come to America with a definite idea of space ingrained in their psyche. They are regionalized and surround themselves with people belonging to similar geographical space or region. We have the Bengali association and the [inaudible] association, etc. In the examination of [Mukherjee’s] fiction, one sees her exploring through her character a fracturing of an already ambiguous identity you have already seen in what I am saying. If you briefly examine [Mukherjee]’s short fiction, say for example, from her collection Darkness, you see characters being constantly shuffled between ideas from their native country and their adopted country. Even when these characters become American citizens, they cannot be “reborn” because of their nativistic beliefs of class, caste, and regional conflict. For example, the character of Lena in [Mukherjee]’s short story “Hindi”. Although Lena marries an American, she cannot live with him because she is haunted by the fact that she belongs to the highest caste of Indian system. On another occasion, when she meets her father’s friend at a party populated by immigrants from other countries, Lena speaks to him in Hindi, but is irritated when the other immigrant guests are familiar with the Indian culture. She notes, “There is a whole world of [inaudible] speaking Hindi.” According to one critic, [inaudible], Lena’s ambivalence of her status in America, on the one hand, expresses a sense of defiance, and on the other, registers a consciousness of the demographic changes in the U.S. because of the large number of immigrants coming from Asia.

In [inaudible]’s other novel, such as The Silent Daughter and Jasmine, she is criticized for giving up characters that are polarized into two groups: the privileged and the under privileged. The underprivileged are the rebellious insurgents of the [inaudible] group that caused much upheaval and turmoil in Bengal in the 1960s and 1970s, and the privileged class are the ones they were fighting against. [Mukherjee] belonged to the privileged class, and in glossing over the lives of the [underprivileged class], we see the subtle invasion of the metaphorical baggage of caste, class, and regionalism Indian immigrants carry with them, regardless of whether or not they are characters of the novel or the novelists themselves.

In the novel, Jasmine, [Mukherjee] is criticized for allowing her protagonist Jasmine to completely erase her Indian past, and assimilate to the predominant white American society. On the other hand, the character Jasmine is uncomfortable when her name is Americanized into [inaudible] or Jazzy. Although [Mukherjee] can be criticized for erasing Jasmine’s Indian identity, one notices the discomfort of the immigrant character and writer when there is total assimilation within the dominant culture, indicating to us that the erasure of one’s past history is impossible, to say the least. [Mukherjee] also tends to blur the distinctions between privileged and underprivileged immigrants through the character of Jasmine who looks for and [inaudible] illegal immigrant Indian woman. She is shown as having similar opportunities and problems as an educated, wealthy Indian woman. According to the critic, [inaudible], [Mukherjee]is making a mockery of the Indian immigrant life in dominant American society. Although in my explanation, if one looks at the lives of Indian immigrant women who are abused and violated by their own culture, for example, in the U.S., such lives are blurred. For example, in both the Hindu and Muslim religions, a code of honor and shame has been a central issue in community dynamics. So regardless of one’s status or locale in society—rich,/poor, suburban/urban, educated/uneducated—women who have been abused have not participated in mentioning the abuser, that [Mukherjee] may have a point in blurring the lines between the victim [plot] and the Indian immigrant.

Ultimately the spatial identity of the South Asian immigrant is blurred as I stated at the beginning of the essay. To further stress the ambiguity of the South Asian, [inaudible] the racial gap of South Asian racial identity and the Asian-American movement, suggests that the race of South Asians has never been clearly defined. Because South Asians do not [fall into] racial categories like every body else–White, Black, Hispanic, Native American, Chinese—they can be inelegantly considered as “ambiguous nonwhite” making them racially marginalized. These so-called racially ambiguous nonwhite immigrants have also been characterized by Pulitzer prize winning writer, [Jhumpa Lahiri] as she [inaudible] records their lives in the United States in a collection of stories The Interpreter of Maladies and her more recent novel [inaudible].

The characters in the Interpreter are, as political and cultural theorist Homi Bhabi would say, caught in the intersections of “marginal places, historical temporalities and subject positions.” [inaudible] uses the example of the Parsees who are a hybridized community, resided all around the globe, and the community to which he belongs. The Parsees, who are predominantly established in India, use Hindu and Muslim rituals and customs while they worship the virgin prophet Zoroaster. In this manner, the Parsees are able to negotiate the cultural identity in India. Similarly, an examination of Lahiri’s characters in her short stories we see them doing the same as they negotiate a space for themselves in the US. [inaudible] story, “The third and final continent,” we note how young Indian students in England cling to their traditions of cooking Indian food and watching Hindi movies as they share a single flat while working on their college degrees. One of these young students then moves to the US after having an arranged marriage in India. He cannot bring his wife to the US until her papers are in order. He lives as a painter with an old American woman in Boston while working at MIT. He has no social life and lives off cereal and bananas. And when his wife arrives, they live a sparkling life, have one son, meets other Bengalis, find shops on Harvard Square that sell clothes and fish, and end up deciding to grow old in America. Yet the narrator ends the story by saying that “a time [inaudible] by each mile I have traveled, each person I have known, and each room in which I have slept.”

Through such characters, we see the beginnings of a [inaudible] the renegotiation of traditions through locality insists on its own self by entering into larger national and social collocations. After a few years in America, the man’s wife in the story does not cover her head, nor does she beat [inaudible] in India. The same couple send their son to study at Harvard yet speak to him in Bengali and decide to grow old in America.

The in-between spaces or imperfections these immigrants occupy are seen in simple changes that they make: [inaudible] instead of writing, sending their son to Harvard, and retiring in the United States. Or as Mary Louis Pratt would say, these people are trans-cultural as they determine what they absorb as their own and what they use it for. Although [hybridity] determines the living in and in-between spaces reduces communities dwelling in these areas from having a single culture, simultaneously the hybridity becomes meaningful as cultures are inter-leagued with one another. Ultimately there are no clear-cut answers. Occupying the liminal space but also lead to ambivalence and antagonism, because negotiating with the difference of the other reveals the radical insufficiency of segmental separate [inaudible] meaning and signification.

We see [inaudible] ‘s ideas of liminality, hybridity and state of in-between-ness fairly well-developed in [Lahiri]’s novel The Namesake. In this novel of society a young man was born in America to Indian parents and lives his entire life unsuccessfully attempting and negotiating a space in American society. Plus the young man is named Gogol, after the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol, and that in itself brings an ambiguity into his so-called Asian identity. As a teenager Gogol changes his name and uses his Indian name [inaudible]. And after that he does not want to be Indian and hates everything his parents do and say. As a young adult, with a lucrative job in New York, he moves in with his American girlfriend, Maxime, and her wealthy parents. He eats only gourmet French foods and assimilates himself to Maxime’s parents and their wealthy friends by spending weekends with them in ritzy neighborhoods in Connecticut. In her article Minding the Gap: South Asian Americans and Diaspora, Singh “quite clearly critiques the south Asian Indian yuppie. This group’s parents came in the 1960s and belonged to the upper class in India. These South Asian immigrants have tried to become white, as they seek overcompensation in real estate and material goods which leads to a sense of liminality in South Asian identity. We note this aspect of overcompensation in Gogol’s character, but despite [inaudible] or his differences in Maxime’s household, Gogol’s liminal identity pushes him to seeking further Americanization, and he ends up leaving Maxime for an Indian woman, thereby positioning himself between inclusion, exclusion, assimilation and segregation, nationalizing and Americanization.

Ultimately, in the larger sense of nostalgia, as Gogol returns to his parents’ home after the death of his father, and after his Indian wife leaves him for an middle-aged Caucasian man. As the reader reads through the final pages of the novel, he or she sees the character Gogol occupying his childhood bedroom and reading, for the first time, “The Overcoat” by Russian author Nikolai Gogol, his namesake.

I think Lahiri ends the novel is more than complex, and [inaudible] because she cannot quite tie the ends neatly while describing the liminal identity such as Gogol’s. Here is a character who portrays the dilemma of the South Asian immigrant diaspora identity which is constantly negotiating cultures that consider him a nonnative status. As for Gogol and other Indian immigrants, diaspora precludes any simple meaning of national belonging because the diasporic itself is situated fault lines. This is neither nostalgia for a home left behind, nor a crude exceptionalism in the host country. As Salman Rushdie claims in his essay, “Imaginary Homeless,” Indian writers writing in English in a country other than their own are able to straddle two cultures. And in doing so they give us characters, plots, and themes that are fractured. According to Rushdie, the idea of an Indian is getting to be a scattered concept. I am in agreement with Rushdie as noted in the lives of the characters that both Mukherjee and Lahiri have created. Their characters separate themselves from their homeland and their culture, as they change their habits [inaudible], such as eating beef or dating Caucasians, or even the case of [Mukherjee]’s protagonist Jasmine and Lahiri’s protagonist Gogol attempting at revising their Indian identity. Rushdie compares such changes to the Christian notion of the fall of man as immigrant writers and their characters become, in Rushdie’s words, “partly of the West.”

I would now, quickly, I just want to talk about an interesting [inaudible] working within the Indian South Asian community which deals with American pop culture. A Chicago Tribune article titled “Teen’s Heritage on Collision Course” shows a popular trend of young Indian teenage girls joining the Miss Teen Indian USA Pageant, which is the first national beauty competition specifically for teenage Indian women. According to one contestant, this is too western a concept but [inaudible] to the future, so she has hidden from her parents. 41 of these young women are, in the words of the article, “navigating a cultural [conflict] “ this is because many of them hail from conservative Indian values and career paths. In my opinion, for these young Indian women growing up in American society and viewing scantily-clad pop divas singing about girl power and sexuality, attending mainstream public and private schools in which proms and school dances are flaunted, yet having to live in homes where their parents are pushing them to follow conservative Indian values puts their identities in flux.

I’m going to quickly spend a few minutes to read my [inaudible]. If we examine certain [feminist] ideas, women such as these teens in diaspora cultures are being marginalized by mainstream popular culture. How? American culture with its glitz and glamour can be viewed as the master colonizer, placing the colonized woman, because she is deceived by the capitalist culture into believing that her space is on that runway as Miss Indian Teen USA. In this way, contradictions are nurtured as the diasporic clash colonized woman is situated outside the center. She is not Miss Teen USA, but Miss Teen Indian USA.

Because of all this, and what I said about the characters in [inaudible] and [Mukherjee]’s writing, and in the life of South Asian women, space of the South Asian community occupies in its adopted resident construct, which [inaudible] cannot be deemed as being entirely stable, as we have seen through the Indian immigrant writers and their characters, and the lives of Indians living in mainstream American society, their identities extend from a sense of place in American society in a constant flux.

Meena Alexander: I would like to thank our speaker-lecturers and we have a minute for questions, if anyone would like to ask questions.

Q&A

Minhaj Qidwai: We were talking this morning about the females, what about the poor males [inaudible]?

Jaskiran Mathur: The poor males or poor females, [inaudible] are definitely part of the same society and it is not whatever designations they have—males, females—both contribute to the present-day situation as it were. There is no social change possible, as I have been trying to emphasize, without including the whole community, which includes the males. If women are empowered to use their own power and not to use men as conduits of [inaudible] male progeny or whatever else, and the fact that they cannot directly represent themselves or directly have a say in their lives, is also [inaudible]. To give you sort of a simplistic response for why women are obsessed with having sons, and why families are, one example require them to have representatives who can have a say in their lives or in their society. If these kind of, if you did not need devious methods to get direct responses, this would not happen. The point is that change, it is not only the women who are feeling change, or women who are the sufferers, or who can become victims of changes when societies are in flux, men do too. They are part of the society. And the only way to see to it that there is nobody is suffering unduly, or there is nobody who is being exploited [inaudible] is to see that things are rationalized, that power is sort of distributed more equitably, and that women can have a say in their own lives.

And so the direct answer to this is statistical: nobody is denying that men are victims of even domestic violence. The statistics are such that there are 98%+ of women are victims and 1%+ of men are. Because obviously, the concern is there. The fire is where the women are, because that is where you are most concerned, that is the fire you are trying to put out first. And hoping that you can make domestic violence of the past, then men will also not be victims of domestic violence. Nobody’s denying that men can be victims, but the statistics are definitely [showing women to be the main victims]. You definitely don’t worry so much about racism in terms of the Caucasian population, it is not that they can’t be victims of racism, they can be, but we are concerned with the minority groups.

Thomas Tam: I have a question to Siona, do you want to comment a little about your love for blue, for women, and for spaces?

Siona Benjamin: Well, I think Sunita covered some topics on space of the immigrant, both it is a dilemma but it is also . . . it is kind of like picture sitting on a fence, where you don’t belong anywhere, but you get this view which is incredible. You feel that you want to belong and you want to be compartmentalized, because it feels safe. But on the other hand, in my work, in a way, it has become a method of decompartmentalizing. So that when I present for example to Asian groups, so to speak, I tend to talk more about my Jewish self, and vice versa. Just because I want to be able to present the other, which I think is not done as much. And also, I think nationalism and all these kinds of “isms” like tribalism, all this kind of really worries me.

Like I said, true art, [inaudible] I mean, I was wondering what art can contribute. It is always supposed to be considered a privilege, “oh you paint, how cute. What do you paint? Landscapes?” Besides that what can art do, what can literature, and poetry and all of that, I think it is a great tool to bring attention to certain issues.

Why do I paint myself blue? Because, to put it in short, I was inspired by the god Krishna, who is the color of the sky, but is also very dark-skinned, so he is often painted kind of a dark blue. After repeatedly being told, actually a little in India but also here moreso, “a Jew from India? Is that real?” Like all Jews were born in Poland, or came from Poland. This is not true. Israel is in the middle East, so you make sense of that. So after being repeatedly told that—repeatedly, being, the whole like, like my husband says, I have to turn it around, you have to prove yourself, and say yes, India is very diverse there are people not only Hindus, you know, [inaudible] India is a country of immigrants and is so cosmopolitan, like I can’t tell you. So after explaining all that, I came to the conclusion that when I started painting the self-portraits, I started wondering what shade of brown I should paint myself. So I said, maybe blue would be a color that stood out and would be a symbol for me as being a Jewish woman of color. So I gradually turned blue.

It is a very convenient color. I mean, instead of trying to hide it, I stand out. I use that as a color or as symbol to bring out certain things. Before, I wouldn’t want to discuss my Jewishness…I mean my Jewishness and my Indianness were two separate things and they were just too complicated to explain. My Jewish life was more like living in a bubble. In India also, even though there was no anti-Semitism in India. My Jewish grandmother lived with all her Muslim neighbors, with the synagogue and mosque right next door to each other, and shared the kosher, the hallah store. They had so much in common. Then she leaves and goes to Israel and her grandchildren are sent to the army to fight against these Arabs who are Muslim. So it is just so conflicting. It’s just incredible. I could never go and live in Israel. Though I do visit it often. I do support the state of Israel, but I do not support the occupation of Palestine. So there are certain issues that you kind of have to draw the line on.

So, kind of like Sunita said in her paper that the spaces that you occupy and don’t occupy come into question. Art has become for me a never-ending well of iconography, both from my Indian mythology, from my Jewish mythology, and all of these symbols that I can recycle so to speak, and create for us a new dialogue, a new language, and rejuvenate it, and give it life again. I mean, how many times have I sat and listened to my rabbi tell stories about certain things, but how do you take these characters and then turn them around and make them characters for today has kind of been very energizing for me.

Parmatma Saran: Have you made an [exhibition] in Israel?

Siona Benjamin: No, actually, I haven’t been to Israel since the late 1980s, the reason being is that . . . actually there are some activist friends, some Jewish peace activist friends who are very involved in the peace movement, and have been jailed for siding with Palestinians, [inaudible] they are trying to bring some of my art over there, or bring me over there, so to be able to, again, become that artist-activist, so that I can, through my art, be able to talk about some issues, otherwise it would be very difficult, for anybody. I have found that it has become a valuable tool or weapon or whatever [inaudible], so I am hoping to be able to go sometime.

Parmatma Saran: That would be a worthwhile experience.

Siona Benjamin: I haven’t even exhibited in India since I left, because my family has dispersed so much that I have no family I can go back to.

Meena Alexander: Any other questions. If not, I think we should give a big hand to our panelists.

Closing Remarks

Parmatma Saran: I would like to certainly thank this panel—very fascinating, very interesting. I wish we had more time to continue the discussion.

When we heard the weather forecast, we were a bit skeptical, Tom and me and some others got concerned about attendance and food and all that, and thought about cutting out a number of food orders that we had placed. But then we decided it was okay to have some extra food. And I was very pleased to see, as I was doing the accounting during the middle of the day, that we had some 60 people in attendance. Out target was 70, so we were very close to our target.

As I said in the morning, Newsweek has come up with an article on South Asian communities. We are now collaborating with them. It is just a coincidence, but we are certainly in good company to have organized this session after South Asian communities.

There are a number of theoretical and ideological questions we need to deal with when it comes to this concept of South Asian community or South Asian identity. A number of people came to us during the break, during the lunch, and because limited time we couldn’t expand on the conversations, but I very much hope you will communicate with us. We have a very active and energetic Executive Director, Dr. Thomas Tam, who really provided leadership in organizing this conference. And Nick, who served as [inaudible] coordinator, and Anthony, as media director here, and some other members of the staff. They really worked very hard, and I wanted to thank them for that.

And last but not least, your attendance and your support was critical. Being a Friday, a snowy and rainy day, many of you came. Somebody came from Florida—my good friend Betty Sung probably cut her vacation short from Florida and came to New York for this conference. So I, we are really grateful, and we hope to continue this process and do some sort of sessions, seminars, and talk about what ideas people [inaudible] and sometime maybe focus on issues that are introduced by SAKHI. When I started my research on Indian immigrants, that was not a major issue, but I think in the last 10 or 15 years it has become, and perhaps it is time to adjust to some of those issues that our communities are confronting.

Again, thank you very much, have a great weekend.