EXACTLY 50 YEARS AGO, as the first English edition of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed was being published in the United States, his friend and fellow educator-activist Richard Shaull noted that Freire’s analysis applied to the U.S. as well as Brazil: “Our advanced technological society is rapidly making objects of us and subtly programming us into conformity to the logic of its system. To the degree that this happens, we are also becoming submerged in a new ‘Culture of Silence.’” (Freire, Paulo, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, NY: Seabury Press, 1970, p. 14).

Looking out at Brazilian society at that time, Freire saw social relations that instilled negative self images that kept the majority of people silent in the face of unfairness and exploitation. Those who had more wealth and status were extolled as deserving of their privileges, ignoring a gamed system that reinforced the idea that those on the margins were responsible for their own fates. Even do-gooders who wanted to help were trapped in their own savior complexes, often starting with the premise that the existing system that had given the do-gooders some advantages also gave them the right to lead the silenced to a better place.

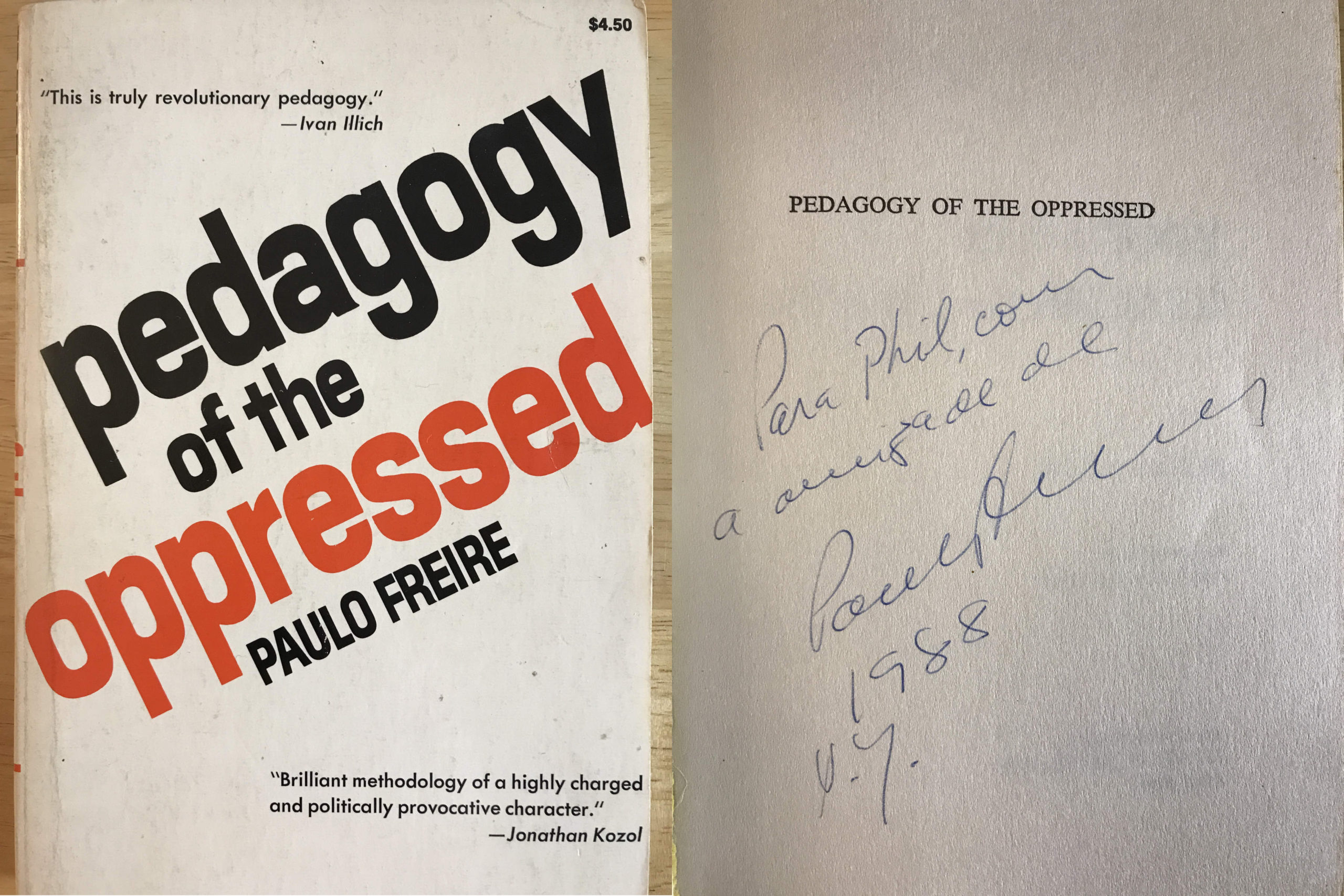

When Freire came to the CUNY School of Law in 1988, he celebrated the critical pedagogy being used to both question why things were in the legal system and also give students the skills to change that system. He reminded students and faculty alike that liberatory education must allow those who have been oppressed by a system of education, or social relations, to develop the consciousness to liberate themselves from the culture that has silenced them.

Recently in the past two months, I have been thinking a lot about Freire’s critique of the “Culture of Silence” while navigating this pandemic world as a teacher, activist and person. While using Zoom to teach my “Asian American Public Policy” class at the University of Maryland and trying to hold “Exit Interviews” with my students as the semester winds down, I have concluded that there are at least five ways that this pandemic is deepening the “Culture of Silence”:

- Increasing passivity

- Promoting shame

- Exacerbating marginalization

- Reinforcing a negative sense of formality

- Decreasing privacy

1. Increasing Passivity

A big problem the last few years in classroom settings has been the tendency of students to hide out from classroom discussions by reading texts on their cell phones or playing games on their laptops. I personally have a rule that no one can do these things during class, reasoning with the students that they are paying their tuition dollars to get some value from each session. And so, if I am not delivering any value, then the remedy should be to provide me some feedback or complain to the administration—not to just zone out.

Unfortunately, when teaching with Zoom, a classroom-replicating online technology, it is easy for students to play games, chat or do whatever they want during the classroom session. Some students leave their screens covered up, citing lack of a functioning webcam, or else they count on my not being able to monitor all of their screens while trying to lecture and coordinate responses via Zoom’s unfamiliar tools.

While students may enjoy the chance to flirt, play poker or catch up on the news during class, my concern is not with these activities, but in the ways that the student is socialized to be passive in the face of opportunities. Paulo Freire recognized that the ubiquitous, pernicious “Banking Model of Education” has bored and pacified students their whole lives—essentially teaching them that knowledge is a social currency that teachers possess and students do not. Students need to have facts “deposited” into their heads like a bank account in order to get ahead. However, as an educator who is trying to help students develop critical reasoning skills so that they can break out of the Banking education model, I’m afraid that even my clumsy use of Zoom for teaching increases the tendency toward passivity and therefore reinforces the Culture of Silence.

2. Promoting Shame

Most of us have seen how the pandemic quickly and effectively pulled back the curtain on inequality in this society. Like the dog Toto in the movie “The Wizard of Oz,” the virus has pulled back the curtain on the fake “wizard” and revealed a world of grotesque wealth and privilege disparities usually hidden by a celebrity culture that falsely tells us that each of us can be fantastically wealthy and powerful, even if we are not born to privilege and wealth.

Unfortunately, instead of making the less-wealthy and less-powerful angry at the rigged game, the Culture of Silence has only increased from the shaming that comes both from inside and outside. For example, during an Exit Interview I conducted for one Asian American student in my Asian American Public Policy class, it turned out that he could not participate in the weekly Zoom classes for several reasons. First, his immigrant parents had lost their jobs and could no longer afford to pay for high speed internet access. Second, he was living in a small apartment with several siblings who needed the one family computer to do their public school homework. Finally, his small apartment afforded no venues that looked neat and presentable on a Zoom video feed, and it would have been impossible to ask his young siblings to stay quiet if he had been called upon to speak at some point during the online class session.

When I pointed out that we could find work-arounds to these issues so that he could continue participating in class, such as calling me from his cell phone and listening in to the discussion, the student declined. The shame he felt was deep, and had been reinforced by seeing the luxurious bedrooms of some of his classmates in prior Zoom conversations. Like the television commentators who place the Oxford English Dictionary on the shelf behind themselves while pontificating on the evening news, some students had gone out of their way to accentuate the privilege in their backgrounds, and this student had decided to just opt out of the game.

3. Exacerbating Marginalization

Classrooms and meeting rooms are more than a place where one person speaks and one or many people listen. Facial clues and other body language are being monitored by everyone in a class or meeting, even if they are not involved in the current dialog. As a teacher, I am constantly scanning the room to see who understands the discussion and who needs to be brought into it. This delicate dance gets easier as one masters an inclusive pedagogy, but every class or meeting session is a new interaction—built on previous ones, but still ripe with new opportunities and possibilities.

In one of my Zoom class sessions taught to 19 students, I allowed them to answer questions for twenty minutes, and stopped to pose a process question. How many men and women had spoken in the first 20 minutes? As it turned out, only two of the first seven speakers were women. Men had dominated a full 17 of the first 20 minutes.

I used this as a teachable moment to help them reflect on the effect of Zoom and similar technologies, which places all the participants in tiny boxes that come to center stage when the person in that box speaks. While the disproportionate participation of males is also noted by researchers in offline classes, I was struck by how easy it is for an otherwise shy female student to just hide in her box and not say a word for the entire class. In this instance, I made sure to call on every student, even the shy ones who were hiding, but it took consciousness on the part of the teacher to make this happen.

4. Reinforcing a Negative Sense of Formality

Teaching is partly a way to transmit knowledge, but also a way to help students develop their own moral and intellectual compasses so that they can navigate their way in the world after graduation. Lots of “learning” takes place in informal conversation before class, after class, and during office hours.

Another positive aspect of informality is that challenging the teacher is easier. As Freire and others have noted, when students are developing their critical reasoning tools, the first person they challenge is the teacher who is promoting this critical reasoning approach. Instead of taking a challenge like “How do you know this?” personally, the liberatory educator sees these challenges as the training wheel moments on the way for a student to be able to challenge bigger authority figures, institutions and practices.

Unfortunately, the public health concept of “social distancing”—a sensible tool for stopping the spread of a deadly disease—has also ended hallway conversations, office hours, and other ways of chatting informally. The Exit Interviews with my students brought back some of that informality, but they were still somewhat formal due to the technological constraints.

For example, one student used her Exit Interview to discuss her career options. I know from discussions after class earlier in the semester that she wanted to go to law school, and has started a political career by running for office on campus. However, she is living at home now with very traditional immigrant parents who want her to follow a safer and more lucrative career path. I could see her censoring herself in her word choices during our Exit Interview, even though mom and dad were not within camera frame. I made sure to not mention her run for office on campus, and made a mental note to send a follow-up email to ask about her law school and political activism plans in a future semester.

5. Decreasing Privacy

Related to the self-censorship displayed by my activist student growing up in a more traditional immigrant household was the self-censorship raised by students who understand the Big Brother implications of internet technologies. One student in my class had to return to his parental home in Asia when the dorms were closed, and the time difference and other factors made it hard for him to attend every Zoom class.

During our informal discussions before and after class in the pre-pandemic era, this student had been very voluble and very aware of the ways that internet communications were being monitored all over the world—including his country of origin. When I communicated with this student via emails and Zoom after he had returned home to Asia, I was struck by the way his persona had been tamped down, and his more critical view of Big Brother-type policies was not verbalized.

Given the limited nature of our communications in the last few weeks of class, it is hard to say for sure whether decreased privacy, or the fear of violating societal norms, had led to the silencing of this brilliant young mind. However, the limitations of communication through Zoom and other issues elevated by the pandemic culture have raised a red flag that must be addressed if we are to continue challenging the Culture of Silence.

Coda: Challenging the New Culture of Silence

You can date a movie by noting the technologies on display: a telegraph from the pre-telephone era, a black-and-white TV from the pre-color TV era, and a phone booth from the pre-cell phone era. Some day in the future, we may look back and wonder how students were taught in the pre-Zoom era.

No matter what the future holds, it is imperative that every liberatory educator, student, and activist reflect on how the tools they are using, and the practices they are following, are either reinforcing or challenging the new Culture of Silence. For example, consider these ideas:

- Challenging passivity: Can you reflect back to your students, colleagues or friends the ways that their actions are reinforcing their own passivity?

- Challenging the notion of shame: Can you help a student, colleague or friend to understand that shame is an internalized way to keep them silenced?

- Challenging marginalization: Can you use process questions to focus a spotlight on ways that individuals or groups are being marginalized?

- Challenging the notion of fake formality: Can you figure out ways to create space for a student, colleague or friend that wants to explore career options and life options that may be beyond those being imposed on them by family or societal constraints?

- Challenging incursions on privacy: Can you create ways for students, colleagues and friends to come to their own understanding of the ways that our civil rights and civil liberties are being constrained in the pandemic age?

Aside from these strategies to help others address these issues, consider how you personally are going to use your time, talents and energies to challenge the new Culture of Silence. As Paulo Friere himself said in The Politics of Education, “Washing one’s hands of the conflict between the powerful and the powerless means to side with the powerful, not to be neutral.” (Freire, Paulo, The Politics of Education: Culture, Power and Liberation, Westport, CTs: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1985, p. 122)