OUR LIVES IN 2020 are being shaped by unfamiliar words, customs and concepts. Many of us are experiencing health insecurity, food insecurity, job insecurity, and fear of random violence.

These concepts may be new to many of us, but they would have been very familiar to my grandfather Misao and many other immigrants and refugees, with or without Coronavirus.

The global pandemic we see today has ripped back the curtain on the yawning divide between those whose wealth, status and privilege affords them a measure of safety and comfort, and those health workers, mail carriers, food service workers, public safety workers, and others who are officially designated as “essential” even as many of them are denied fair wages, job protections, healthcare, child care, safety equipment, and equal access to the digital world.

We can explore these concepts through the life of one immigrant, my grandfather Misao Tajitsu, and the world inhabited by his grandson today.

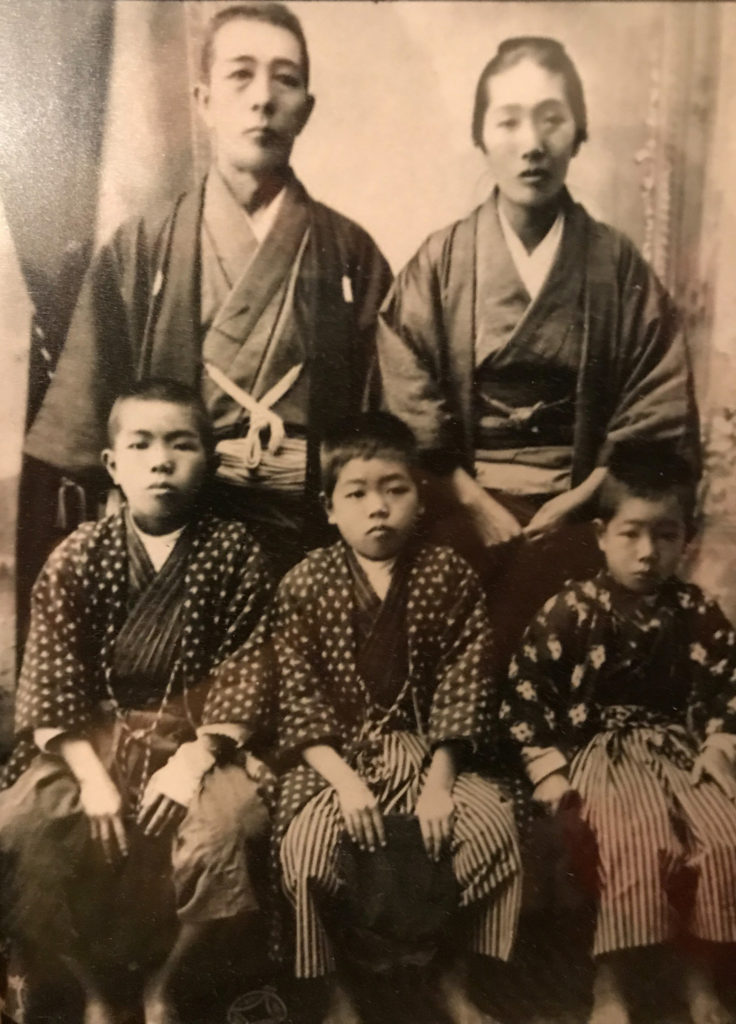

Kagoshima 1908

It is springtime in Kagoshima, located on the tropical southern tip of Japan. You are used to the salty warm air, the sight of Mt. Sakurajima overlooking the bay, and the sound of surf lapping against the shore.

This morning, you are huddled in a dark shed at daybreak with a few dozen others. By nightfall you will be on board the ship rocking nearby, headed to a place none of your family has ever seen. The comfort of your bed, the familiar voices, and the bustling of activity in your parents’ kitchen will be missing. You will be alone, even as you share close quarters with hundreds of strangers.

“Tajitsu Misao!”

You hear someone call your name.

“Over here,” you reply, as dozens of eyes from across the dimly lit room turn your way.

You stand up, walk around a sleeping body, and head toward the man at the desk.

New York 1972

As a student intern in the American Museum of Natural History’s Vertebrate Paleontology lab, I was studying and curating the tiny jaws of rabbits who lived 30 million years ago. We would use the picks you see at your dentist’s office to scrape sediment off the specimen. Then we would write on a note card whether this was a left or right jaw and which teeth were present. Finally, we would carefully write a specimen number on the jaw with a tiny Rapidograph pen and then cover it with a coat of glyptol varnish. The whole process took just a few minutes, but there were thousands of specimens to process.

I whiled away the day by listening to the senior staff members as they discussed the latest developments in geology and paleontology, and one concept, in particular, caught my attention. Curator Niles Eldredge had just teamed up with famed evolutionary biologist, Stephen Jay Gould, to come up with a geologic concept known as Punctuated Equilibrium.1

Seattle 1908

Grandpa Misao landed in Seattle to start his new life. I don’t know all the details because he died when I was seven, and none of my elders talked much about their lives in the old days.

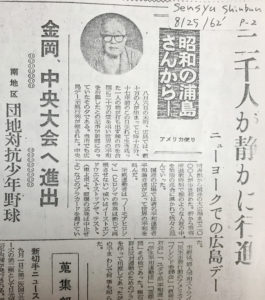

One story I have heard is that he was a pacifist and decided to leave an increasingly militarized Japan that had won wars against China in 1895 and Russia in 1905. As the eldest son of a family with some privilege, he was giving up his primogeniture rights to land and other valuables. Yet, he somehow maintained ties to his community by writing a column for a hometown Kagoshima newspaper, under the pen name Showa-Urashima san, that detailed his life in the United States, with the proceeds used to maintain the Tajitsu family burial plot. When he returned to Kagoshima many years later, he was still given the privileges of the eldest son, which he used to welcome a younger brother’s wife into the family, even though she was from a lower class.

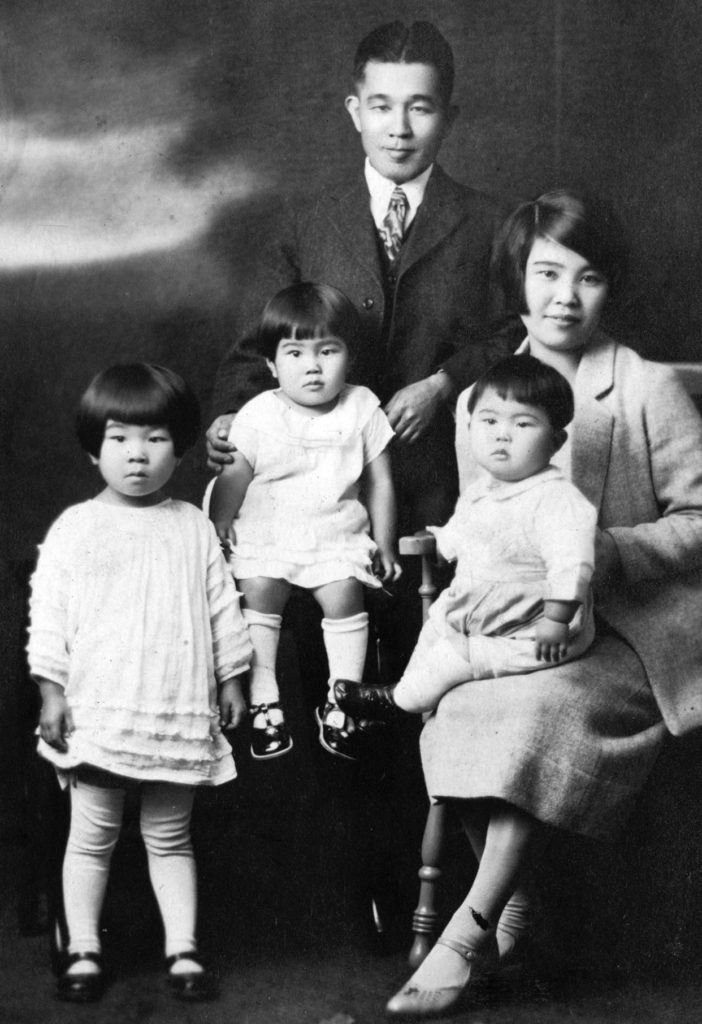

Despite his education and advantages in his early years, Misao had to start over when he arrived in Seattle at age 21—working as a houseboy, dishwasher and hotel bellboy. When he got a $5 tip for washing the back of a visiting Japanese dignitary one day, he dutifully sent it home to his mother in Kagoshima.

Misao had learned some English before he left Japan, but he still spent decades driving a paneled van to sell wholesale groceries to restaurants and grocery stores. One positive aspect of having a van, however, was that he got to drive my mom and her friends to school events and Girl Reserves meetings all over the Seattle area.

World War II

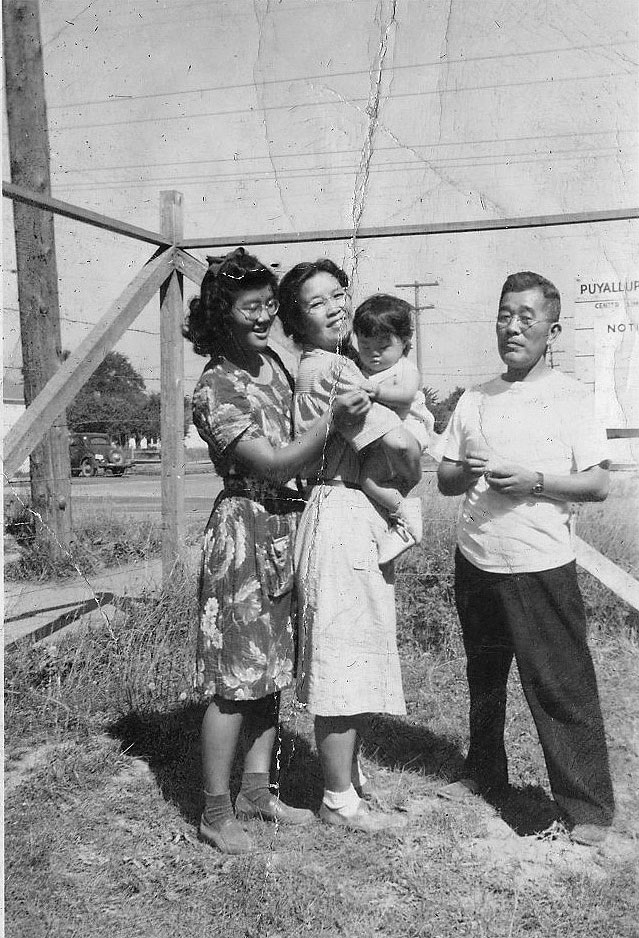

Another major turning point in Grandpa Misao’s life was the forced uprooting and incarceration of the Japanese American community during World War II. I have a faded picture of him with Grandma Ritsu, Uncle Ronnie, and Aunty Uta standing behind a barbed wire enclosure at the Puyallup Racetrack near Seattle in 1942. Grandma and Uta offer a semi-smile to the camera, but Grandpa looks back at us with an expression of composure and warmth, mixed with the uncertainties and trepidation he was no doubt feeling. At age 60, his Japanese ancestry and American laws that prevented him from becoming a citizen meant that he was in legal limbo, potentially to be separated from his five children who were American citizens by birth. Where he was headed and what lay ahead were unclear.

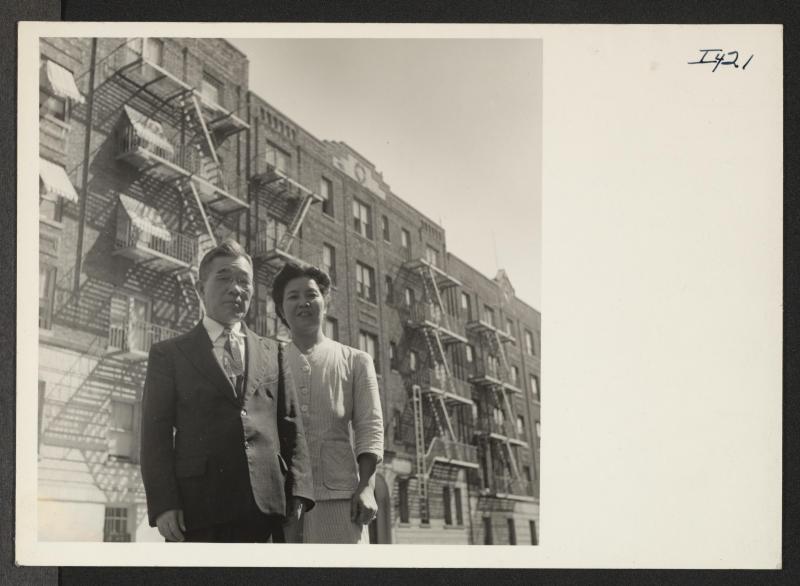

I accidentally found photos of Grandpa Misao and Grandma Ritsu online about a decade ago when the University of California decided to post photos from the archives of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the federal agency that had overseen the holding of 120,000 Japanese Americans behind barbed wire during WWII. One photo shows my grandparents in their Sunday best, standing in front of a tall New York City apartment building in 1944. Another shows them inside their apartment, amiably chatting with two other Japanese American neighbors. A third shows Grandpa and 17 other members of a racially diverse “Temporary organizing committee of the Greater New York Citizen’s Committee for Japanese Americans.”

Source: Online Archive of California

I was thrilled to find these photos—and still am—but was dismayed to realize later that these were propaganda photos taken by the WRA to convince Japanese Americans still in the barbed wire-enclosed camps that they could safely leave the camps and come to East Coast cities such as New York. The West Coast was still full of whites who had grown up on “yellow peril” journalism and who blamed Japanese Americans for wartime actions by Japan that they had no control over. Fortunately, my grandparents had family members already living in New York, so they were able to make this transition more easily than some others. Yet, at age 60, Grandpa Misao was starting over yet again, now as a packing and shipping clerk at the National YMCA Press.

Grandpa Misao was already in his seventies when I was still a young boy. I can visualize him listening to the Mets baseball game on a white reclining yard chair behind my parents’ house in New Jersey on a sunny day. However, the most lasting image of him came when I was seven years old and he was now reclined in a coffin. I had never yet had a close relative die, and had never seen my mother cry so much. I had terrible dreams for months, and it was only after I saw his diaries, copies of his articles in the Kagoshima newspaper, and other mementos from family scrapbooks years later, that I was able to see his life as a whole. Despite the punctuations caused by war, emigration, forced removal to the WRA camps, and a cross-country move to re-start life again in New York City, he had raised a family, served his community and chronicled the world as he saw it.

Punctuated Equilibrium

Instead of seeing evolution as an incremental process that progresses at a steady rate, the Punctuated Equilibrium theory describes change as a long period of evolutionary stability punctuated by a short period of intense change activity (branching speciation) that sets the stage for the next long period of stasis. This concept explains why intermediate forms may not be found in a fossil record, as gradualist theories of change might expect.

I didn’t think much about Punctuated Equilibrium after I went to law school and started work as a social change activist, lawyer and teacher. Many of the issues I dealt with, such as immigration reform, preventing anti-Asian violence, and redressing the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, took years of effort to get incremental change.

However, the current confluence of crises related to public health, race, economics, global climate, and the role of the military/police have made me look anew at the notion of Punctuated Equilibrium as a possible way to explain social change processes. Looking back through history, for example, there have been technological advances, political revolutions, battlefield victories, healthcare disasters, economic disasters, and racial justice victories that have literally hit the societal “Restart” button and forced changes in many aspects of life. Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones,2 Connie Gersick,3 Michael Givel4 and others have written about how Punctuated Equilibrium can be applied to concepts such as politics, policy making, and management, but none of the events or eras they describe compare to the events now unfolding in 2020.

São Paulo 2015/2018

I stopped at the Museum of Japanese Immigration in São Paulo on my way back to the United States in 2015, and saw a database screen that invited you to find information about your Japanese-Brazilian ancestors. I kept on walking by the screen, but my wife was curious. She had been coming to Brazil since the early 1980s to study the Wauja indigenous community in the Amazon rainforest and, in fact, we had just returned from a visit there to collaborate with the community to preserve its culture and Arawakan language. However, this was the first time she had visited the huge Nipo-Brasileiro community in São Paulo, which is the largest enclave of Japanese-derived people living outside of Japan.

“Let’s enter the name ‘Tajitsu,’” said my wife, as I kept on walking past the database screen.

“Go ahead,” I said, “but you aren’t going to find anything. Tajitsu is a very rare name even in Japan. Anyone who has that name is probably from the Kagoshima area where my grandparents grew up and is probably related to me. But Grandpa Misao is the only one who left Kagoshima to go east, and he landed in Seattle.”

And when she entered “Tajitsu” into the database, four names popped up. Over the next few years, I used the internet, snail mail, and contacts at the Museum of Japanese Immigration to locate the descendants of the Tajitsus who had left the docks in Kagoshima at the same time as Grandpa Misao, but headed for the plantations in Brazil.

Fast forward three years to 2018. It is 6:00am and my wife and I are just stepping off an overnight United Airlines flight from Washington D.C. to São Paulo. We pass through customs, burst through the International Arrivals door, and immediately scan the crowd. Waving excitedly from one side were two of my Tazitu cousins.

Why Tazitu? The Japanese kanji characters were the same as the ones that Misao had used to spell his family name, but “Tazitu” is in line with one way of transcribing Japanese ideographs into “romaji” (roman letters/alphabets), and

“Tajitsu” is based on the other.5

During several hours of conversation that was held mostly in Portuguese, punctuated by a little English and Japanese, my wife and I were able to learn about the relatives who had come to Brazil at the start of the 20th century. Afterwards, I had several joyful reunions with other Tazitu relatives and conducted archival research at several Nipo-Brasileiro organizations in São Paulo. The result was an awakening to over 100 years of Tajitsu family history in South America. For example, one Tajitsu blacksmith had gone from Japan to Brazil but later returned to Japan. Another went to Brazil and then moved with his wife to Buenas Aires, Argentina.

I have kept in touch with the Tazitu cousins, and, in fact, one of them now lives in the U.S. in Vermont. When we held a virtual Tajitsu/Tazitu family reunion using Zoom a few weeks ago, it included relatives from both the North and South American branches of the Tajitsu diaspora.

2020 Restart

There has never been a moment in history like 2020 when the “Restart” button has been hit in so many ways and in so many locations all at once. The COVID-19 virus has affected people in every corner of the planet. Thanks to global communications, the police killing of George Floyd has sparked a rethinking of racial justice and police tactics all over the world. The abrupt closing of economies has created opportunities to re-think how we approach economics and global climate priorities from the ground up.

The net effect of hitting the Restart button in so many aspects of life presents an unprecedented opportunity for re-thinking and re-prioritizing race, economics and many other aspects of our lives. Of course, those who previously enjoyed various privileges would love to simply return to the bad old days pre-COVID-19, but the massive Black Lives Matter protests by people of all backgrounds, locations, and interests means that this will not happen. The Overton Window6 of policies acceptable to the mainstream population has shifted dramatically in the past two months, and there is no going back.

What these recent events mean for all of us is that now we all are immigrants. Some of us have migrated from the analog environment to the strange new digital world that only our children fully understand. Some of us are whites who can see white privilege for the first time, or African Americans who are entering a world of new possibilities. They have made the connection and then taught the rest of us that until Black lives matter in a society which has unjustly enriched slaveholders and their descendants, none of us can be truly free.

As a grandson of Misao Tajitsu, I already know that life as an immigrant will sometimes be hard and unpredictable. The difference between my life and his, however, is that I will be going through this immigration experience with every single person on the planet. All of us are stepping into a world we did not grow up in. All of us will have to learn new terms, new customs, and new ways of being.

I will do my best to make sure that compassion, justice and respect for our planet and all of its people form the bedrock of this new period of stasis. And I hope that once this new stasis is achieved, that it will last a long, long time.

Coda

So, how do we live as immigrants to this new equilibrium? Here are my personal plans:

- Study my family history to see how historical forces have shaped my world

- Decide how best I can use my skills and energies to build a better world and push the Overton Window of achievable policy alternatives in a positive direction

- Figure out how to sustain myself and my loved ones as I help to build this new world

- Figure out ways to work both inside and outside the system, depending on what is needed at any given time

- Look at my list of friends and colleagues, with all of the intersectionalities7 they represent, and think anew about what I can do to help them achieve their goals as well

Notes

[1] Stephen Jay Gould, “Punctuated Equilibrium—A Different Way of Seeing,” New Scientist 94 (April 15, 1982): 137-139.

[2] Frank Baumgartner and Bryan D. Jones, Agendas and Instability in American Politics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993).

[3] Connie Gersick, “Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development,” Academy of Management Journal 31 (October 1988): 9-41.

[4] Michael Givel, “Punctuated Equilibrium in Limbo: The Tobacco Lobby and U.S. State Policy Making From 1990 to 2003,” Policy Studies Journal 43:3 (2006): 405-418.

[5] There have been two major ways of spelling Japanese ideographs in the Latin alphabet (what the Japanese call “romaji” or roman letters/alphbets). “Tazitu” is in line with what is called the “Kunrei-shiki” system sanctioned by the (old) Education Ministry in Japan. “Tajitsu” is based on the system created by James Curtis Hepburn (1815-1911), a Presbyterian medical missionary, and author of a widely-used Japanese-English dictionary. Today, the Hepburn system is common in Japan, but some people prefer the “Kunrei-shiki” version of names. So, the Tazitu/Tajitsu difference probably started back in Japan, and was not a result of a difference between English and Portuguese speakers. [Thanks to my friend and Japanese labor journalist Mr. Norio OKADA for this helpful information.]

[6] Maggie Astor, “How the Politically Unthinkable Can Become Mainstream,” The New York Times, February 26, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/26/us/politics/overton-window-democrats.html.

[7] Kimberle Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Issue 1, Article 8 (University of Chicago Law School, 1989), http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.