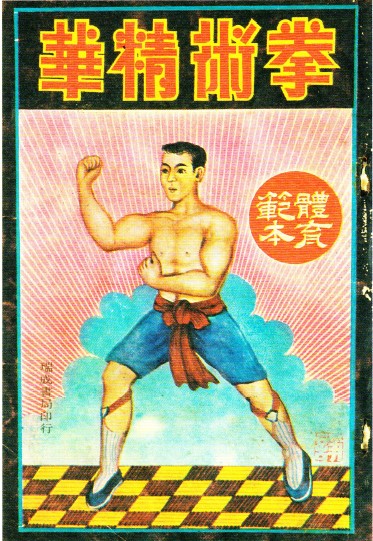

Printed in Taiwan by Regent Publishing (瑞成書店, 1973)

Living and breathing martial arts has always been my life. The practice of learning, drilling, sparring, and community at the dojo all provide me with an awakened sense of calmness.

AFTER THE IMPLEMENTATION of the national shelter-in-place directives in the U.S., my martial arts ritual and routine was rudely interrupted. On a larger scale, many dojos across the nation have halted training completely due to the risk of infection. We no longer train the way we used to, nor can we enjoy the camaraderie of tough sparring we had before the COVID-19 outbreak. Such limitations have left me thinking more deeply about martial arts: its origins, the reasons why I train, and in light of the increase in anti-Asian hate crimes, why martial arts training has become even more necessary to protect body and spirit.

I. Martial Arts Form and Philosophy

“知可以戰與不可以戰者勝”

“Those who know when and when not to fight: Victorious.”

Among the various forms of martial arts, Wing Chun has witnessed a rise in popularity due to recent depictions in movies of its most famous practitioner, Ip Man (1893-1972), Bruce Lee’s first master. According to Ip Man’s testimony in his book Origin of the Wing Chun Style, Wing Chun was founded by a woman named Ng Mui (1623-?) who fled the Shaolin Temple after it was burned down by the army of the newly founded Qing dynasty. Likewise, one seventeenth-century historical account suggests that Wing Chun was founded by a woman named Ding and her husband. This account further notes they had a total of twenty-four disciples, including a man named Zheng Li who possessed extraordinary strength and martial prowess.1 The description of Zheng Li has a certain appeal to our modern sensibilities. He embodies what we envision to be a martial arts hero: strong, courageous, and masculine. Yet what we find in many martial arts, including Wing Chun, is not a focus on brute strength and rough “male” qualities, but an emphasis on gentle characteristics and flowing movements that speak to commonly shared technical and philosophical principles among martial arts forms.

The methods of Wing Chun emphasize how to divert force and use quick strikes to tire out and demoralize one’s opponent. If this martial art exemplifies certain feminine, gentle qualities of fighting, then Chinese Shuai Jiao is certainly its masculine counterpart. Shuai Jiao is a combat wrestling system where strength, explosiveness, and physicality are significant factors in executing fighting techniques. Shuai Jiao was the core training program for the army in many Chinese imperial dynasties, and in current times, it is still taught in military and police academies in China and Taiwan.2

From Shuai Jiao, Wing Chun, and Judo, to Muay Thai, Pankration, and Boxing, these arts are living, organic, and ever-transforming fighting traditions. When we consider the historical contexts of these arts, they were certainly designed as effective tools for combat. Despite their strong focus on training one to control and adapt to the chaos of combat, the inherent principle of “martial arts” is quite the opposite of aggressive fighting. In The Art of War, Sun Tzu stresses avoiding directly attacking enemy forces and to instead counteract the enemy’s mind as the greatest offensive.3 He reasons that direct, belligerent offensives only serve to generate casualties on both sides, which is the worst consequence of fighting and is to be avoided at all costs. Sun Tzu summarizes the ultimate objective of martial arts in one concise phrase: to “subjugate one’s opponent without fighting” (buzhan er quren 不戰而屈人).4

Readers of The Art of War will find Sun Tzu repeatedly emphasizing this guiding principle of martial arts: to prevent conflict, war, and damage on both sides. The breakdown of the Chinese character “martial” (wu 武) further resonates with this principle. Wu is made of two radicals: “prevent” (zhi 止) and “spear” (ge 戈). Thus “martial” in Chinese emphasizes the tremendous importance attached to preventing hostility of any kind.5

Warring States Period (475-221 BC)

When applied to modern fighting, the character “martial” speaks to the fundamental need to train martial arts for protecting the bodies of oneself, our families, our friends (and in ancient times, one’s lord), and to protect our spirits by pursuing the Way (dao 道). For practitioners of martial arts having East Asian origins, the aim is to become what Confucius had outlined in the Analects: a “gentleman” (junzi 君子) who is humane (ren 仁) and embodies propriety (li 禮) in his words and actions, and who is gentle but capable of toughness (rou er neng gang 柔而能剛).6

Likewise, another ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu tells us that a person’s ultimate aim is to give “undivided focus to vital breath and achieve the utmost degree of gentleness” (zhuan qi zhi rou 專氣致柔), and to model water in its fluidity and ability to overcome hard things.7 Certain human qualities and fluidity in action were considered to be pinnacles of human development by martial arts practitioners in Japan, as seen in the development and maturity of several “Gentle Art” (jujitsu 柔術) traditions and its branching form, the “Gentle Way” (judo 柔道),8 which both acknowledge the necessity of hard force (pushing, pulling, throwing), but prioritize gentle maneuvering (countering, off-balancing, diverting force).

The purpose of such martial arts is to train a person, usually of smaller stature, to dominate a larger, stronger opponent in the most efficient, smooth manner possible without reliance on brute strength. With enough training, he will be able to block aggressive strikes, redirect an opponent’s force, throw him to the ground, and force him to submission, thereby preventing rather than prolonging hostility.

II. An Empty Dojo and My Only Training Partner

“知己知彼:百戰不殆”

“Know yourself, know your enemy: win one hundred battles.”

The dojo (道場, literally a site where the Way is practiced) is a site for ethical and spiritual cultivation. Traditionally it was considered both a space where Buddhism is studied and a combat training hall. The goal of working through the physical and mental tempering during training is to acquire the highest of human qualities, including those described by Confucius and Lao Tzu. At the same time, with the influence of Buddhism, combat training can also be viewed as a physio-mental activity, capable of assisting practitioners in uncovering pathways of their interior landscape and capable of taking them to a higher state of consciousness. It is certainly a place to learn ways of fighting, but can also serve as a pure space for cultivation in emptiness (kong 空) / nothingness (wu 無).

These days, the dojo is mostly empty due to COVID-19. In the absence of training partners, I often drag out a 180-pound worn-out and sturdy training dummy who graciously allows me to beat him up a couple times a week. I run through about ten fundamental techniques and drills to keep my mind sharp and muscle memory active. I stand him up, make grips, and take a deep lunge forward to unbalance him, then sweep out the dummy’s legs to send him crashing down into the mats with a deep, thunderous boom. Immediately I drop a knee into his “ribs” and punish him with a flurry of strikes to the head and transition into lapel chokes and joint submissions.

When executing my techniques, even on a training dummy, I think of nothing. I am not checking John Hopkins University’s Coronavirus Resource Center case tracker map. I am not thinking about anti-Asian racial slurs, assaults on Asian Americans, and “Kill the Chinese” chants. To the best of my ability, I practice life and death as an Asian American Martial Artist.

III. Food, Face Masks, and Fighting

“出其所不趨,趨其所不意”

“攻而必取者,攻其所不守也”

“Appear in places where he must hasten, hasten to places where he is unprepared.”

“To excel in attacking, attack where he does not defend.”

When not training, I am a serious food glutton with a diet completely antithetical to what is expected of a martial artist. I sometimes tell my friends that in martial arts, especially for practitioners in China, a fighter’s martial prowess is often considered to be consummate with his capacity for large amounts of meat and wine. This joke is related to images of heroism and masculinity that are prevalent in Chinese literature, such as the classic novel Water Margin, where the “monk” Sagacious Lu swings around a 100-kg staff with god-like strength and causes a ruckus at the Wutai Monastery, and the “pilgrim” Wu Song who wrestles and defeats a tiger with his bare hands on Jingyang Ridge (as well as the martial heroine Chen Liqing who uses her superior fighting skills to wrestle, wristlock, and defeat a strapping bandit-hero named Wang Ying the “Short-Legged Tiger”).9 These heroic feats occur, of course, after these heroes have consumed several plates of meat and buckets of wine.

Water Margin (1614 edition)

My commitment to the martial arts began as a fascination with martial heroes and heroines in classic Chinese novels.10 This interest in the intersection between martial arts and literature led me to spend about four years in China and Taiwan. Now I live in the Southwest region of the U.S. with my family. My wife and I are almost always in search for some semblance of our family’s Chinese/Taiwanese cuisine favorites. A constant topic we have is our yearning for the plethora of unique, vibrant dishes and snacks from our respective native places. Often our weekends turn into journeys for the perfect Taiwanese-style fried chicken, fried tofu, black rice, and boba tea. At times we search for cuisine tailored to my Hong Kong and Guangdong roots: Cantonese-style BBQ duck and pork, dim sum, and the classic HK-style milk tea (again, the antithesis of a martial artist’s diet).

Much of our marital harmony has been built upon our love for “Southern” Chinese cuisine. Yet with the “Stay Safe, Stay Home” directive, we no longer dine at our favorite Asian restaurants. Gone are the days of casually strolling the Asian market in search of food from our respective homelands. Instead, we wear face masks to protect ourselves and to protect others during our now infrequent Asian market trips. We also decided to wear unique items: a baseball cap declaring “Taiwanese” for my wife (in her view, to not be mistaken as “Chinese” and to avoid getting attacked), and for me, a U.S. battle flag neck gaiter that covers my face and highlights my American “patriotism.”

We live in a predominantly white, Christian, and conservative area, so the fears of anti-Asian hate crimes are a constant reality for us. On occasion I walk through the grocery store with my wife and daughter in hand. My wife wears her face mask and “Taiwanese” baseball cap, and my daughter wears a child-sized face mask. With the U.S. battle flag neck gaiter draped across my face, I walk tall, constantly scanning for potential aggressors. On the exterior I am calm, but I cannot shake off my uneasiness—the sense that we are being watched, judged, and vilified.

At home, a reel tape in my head plays: on March 14, 2020 in Midland, Texas, a man draws his knife and stabs an Asian American family of three. He assumes they are Chinese, blaming them for spreading the Coronavirus. In reports detailing anti-Asian hate crimes that have occurred during COVID-19, a common narrative is prevalent: Asians are victims (not capable of defending themselves), not martial arts heroes/heroines; Asians are weak, not staunch or courageous. In these narratives we are represented as a failed people who cannot shelter our bodies, protect our spirits. The damage is visceral. Fears bubble up somewhere deep: a darkness gnawing at the soul.

Is my choice to don a U.S. flag informed by fear or patriotism? Perhaps that darkness can be purged if other American see me, born and raised in the U.S., as one of them. Covering my face with a U.S. flag makes me unreadable, temporarily unafraid. Yet by concealing my face, I also surrender my Chinese American identity, and the nuanced differences of the regional groups to which I identify with (Hong Konger, Taiwan Supporter, Southern Chinese) gradually diminish as well. In light of the pandemic, fears of the foreign-born Coronavirus continue to grow, and we are read by the rest of America as a collective without differentiation, read as all Chinese.

The reel tape in my mind plays again. Shelter your body, protect your spirit. I imagine myself faced with the aggressor in Midland, Texas, who has just pulled out his knife. The aggressor comes at me with an obvious intent to hurt.

The many hours of training at the dojo kick in.

I put my hands up and step into my kamae (postured fighting stance), which is perfect for blocking and maneuvering around my opponent. With the knife he stabs in an overhead motion, but I dodge, deflect, control his arm and wristlock to disarm the weapon. I close the distance, sweep out his legs, and keep him pinned to the ground. In this dominant position I am completely capable of executing a carotid choke, or attacking elbow or shoulder joints if needed. The onlookers stare. Some are recording on their smartphones. I hope they notice the U.S. battle flag covering my face. I hope they see a fierce, patriotic Asian American.

We have done these drills hundreds of times in many different variations and have applied them in live combat. We train to prepare for hostile situations, yet these activities also elevate us beyond that darkness gnawing at the soul. I fight with the intention to protect, without the desire to hurt; I accept the existence of my fear and I commit to the belief this fear will not cripple me. I work on becoming “without mind” (mushin 無心),11 a complete, formless state that transcends language and logic. In drilling, sparring, or meditation, we hope to enter mushin, where past and future take no relevance, where human activity becomes “action without contention” (wuwei 無為).12 That way, even before hostility presents itself (with or without a weapon), we have already won the battle in our minds.

May 3, 2020

Notes

[1] Benjamin N. Judkins, “Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (9): Woman Ding Number Seven: Founder of the Fujian Yongchun Boxing Tradition,” Kung Fu Tea, November 14, 2019, https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2019/11/14/lives-of-chinese-martial-artists-9-woman-ding-number-seven-founder-of-the-fujian-yongchun-boxing-tradition/.

[2] “History,” Chinese Kuoshu Institute, http://www.kuoshu.co.uk/History%20-%20SJ.htm; “History of Shuai Jiao,” Traditional Wing Chun Kung Fu Academy, http://traditionalwingchun.com/twckf/history-of-shuai-jiao/.

[3] That is, to counteract his mou 謀, or “strategic maneuverings.”

[4] In my translations of The Art of War passages, I have referenced Ralph D. Sawyer’s translations in The Art of War (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press Inc., 1994).

[5] This point is noted in the early Chinese historical narrative Chunqiu Zuo zhuan [Zuo Commentaries for the Spring and Autumn Annals]: “[The true meaning of] war lies in the prevention of hostilities” (zhi ge wei wu 止戈為武).

[6] May Fourth writer, intellectual, and scholar Hu Shih (1891-1962) writes: “Confucius came from the scholarly tradition of the Gentle Way and hoped people would be gentle but capable of toughness, gracious and respectful.” See Hu Shih’s Shuo Ru [Discourse on Confucians] (Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiu suo jikan 4, 1934).

[7] See Wang Bi, Laozi sizhong [Four editions of Lao-Tzu] (Taipei: Da’an Chubanshe, 1999): 7.

[8] See Budō: The Martial Ways of Japan (Tokyo: Nippon Budokan Foundation, 2009): 123-138.

[9] A character from the Water Margin sequel titled Dangkou zhi [Quell the Bandits], by Yu Wanchun (1794-1849).

[10] I use this as a kind of umbrella term that covers cuisine from Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

[11] This view of Mushin is based on the school of the Sixth Patriarch Dajian Huineng (638-713). See Deng Keming, “Tang Dai Huangbo Xiyun chanshi zhi xinti guan” [Tang Dynasty Zen Master Huangbo Xiyun’s Perspective of Mind and Body], National Taiwan University Buddhist Studies, No. 22 (Dec. 2011): 3.

[12] Sometimes translated as “non-action.” The original passage emphasizes how ancient sages managed human affairs without action and suggests they governed with maximum effect with the lightest touch and least amount of effort. See Laozi sizhong [Four editions of Lao-Tzu], 2.