“THE CURIOUS THING ABOUT PANDEMICS,” I read in a back issue of The Guardian, “is that novelists don’t seem to know what to do with them.” Well, that is one of the curious things about pandemics. “But when they have written memorably about them,” the critic continues, “it tends to have been as allegories for something else – fascism, say, or war.”

This article is only a few months old, but already recalls a distant past—a time when the coronavirus was new, when the pundits were weighing in with their choice of pandemic fiction, when ever more hashtags were horning in on the action: #Dystopia, #PostApocalypse, #SickLit, #TerminalRomance, #QuarantineLife, etc.

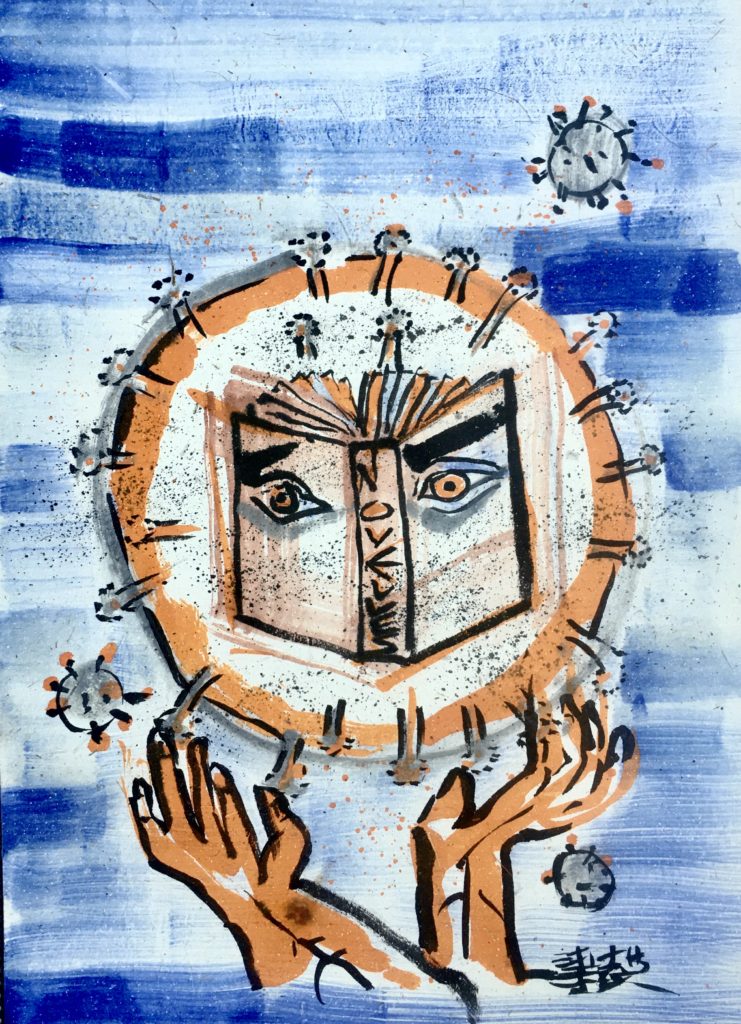

But now that we’re into the next phase of literary speculation, the big question before us is: What new species of fiction COVID-19 will spawn. Simply put: How will the novel coronavirus mutate into the coronavirus novel?

The answer, I submit, stares us in the face. Coronavirus, the novel, is already being churned out in spades, at top speed. This is facilitated by its intrinsic form, which is short. Very short.

No, I am not referring to the COVID haiku, the other short form of pandemic literature forged, for example, in writing workshops for New York City care workers, cabbies, subway attendants, and other front-line workers during the worst spikes of the virus:

Bangladeshi men

Deliver tacos

Better days, Upper East Side

Rats, humans vie for space

In urban sidewalks

Cracks in tenement walls

No opera now

the virus darkened the Met

but birds sing to me

Such seventeen-syllable dispatches pack a narrative punch of their own, but are not to be confused with the coronavirus novel, even though both consist of a three-line block of text. The formal difference is that unlike the C-haiku, the C-novel is restricted only by the number of lines, not the number of syllables. The other essential difference between the two literary genres is that while the haiku is merely short, the coronavirus novel is often nasty, brutish, and short. I am not saying that all haiku conform to a kinder, gentler form of ‘short’—especially not when I recall Richard Brautigan’s Haiku Ambulance:

A piece of green pepper

fell

off the wooden board salad bowl:

so what?

Cruel. But enough of haiku. The beauty of the coronavirus novel—its incomparable genius—is that it writes itself. Here’s a random sampling:

Song Yingjie, a 28-year-old pharmacist in Wuhan; Wang Tucheng, 37, a doctor in Henan; and Xu Hui, head of a virus control unit in a Nanjing hospital, are all dead. Coronavirus? No, cardiac arrest from exhaustion.

Reading that masturbation boosts the immune system, a Chicago man struck down by Covid-19 reflects on social media that: “a) this is obviously not true, or b) I’ve saved myself from certain death.”

In Hong Kong, recent infections included a 40-day-old baby, a domestic short-haired cat, and a domestic worker who was infected by her employer’s teenage son.

In a new case of weaponized saliva, federal authorities in Florida have charged a man who spat on the face of a police officer, falsely claiming to have coronavirus, with perpetrating a “biological weapons hoax.”

In Thailand, Health Minister Anutin Charnvirakul says ‘dirty’ Westerners are spreading the disease around the kingdom, long a mecca for Western tourists.

To visit his sick father in Kashmir, Mohammed Arif, 30, set out from Mumbai, 1,300 miles away, on a battered Hero Ranger bicycle toting a small rucksack and the equivalent of USD 8.00. He has yet to arrive.

You may mistake the above for COVID-related news fillers (or ‘squibs’ as they were called in newsrooms back in the day). If so, you can be forgiven. The prototype for these three-line narratives is traceable to an early 20th century journalistic phenomenon in France: the faits divers. These were ‘true-life’ stories in the tabloid tradition, usually found on the back pages of newspapers, or ‘sundry events’ as they were known in English. “Fragments of novels,” Roland Barthes pronounced them. Perhaps he was thinking of the fait divers on which, allegedly, one of the great novels in the Western cannon was based.

See if you can match the following fragment with its famous offspring:

Delphine Delamare, 27, wife of a medical officer in Ry, displayed insufficient austerity. Worse, she ran up debts. To avoid paying them, she took poison.

Answer: Madame Bovary. (I’ll admit this was news to me too.)

In a later classic of modern literature—Albert Camus’ The Stranger—we are introduced to a more fleshed-out fait divers. Meurseult, the anti-hero, is in jail waiting to be executed for the crime of murder (and also, it seems, for the crime of failing to cry at his mother’s funeral)—when he finds, stuck to his mattress, a scrap of old newspaper he can’t help reading again and again.

The story is about a man in Czechoslovakia who returns to his village after a twenty-five year absence. Thinking to surprise his mother and sister, he books a room in the small hotel they run, but under an assumed name. Over dinner, the stranger—whom the women still fail to recognize—can’t resist throwing around large sums of money to impress them. The women wait till later that evening to relieve him of it all. First they bludgeon him to death with a hammer; then they fling his body into the river. The next day, on discovering the man’s true identity, the mother promptly hangs herself, and the sister throws herself down a well.

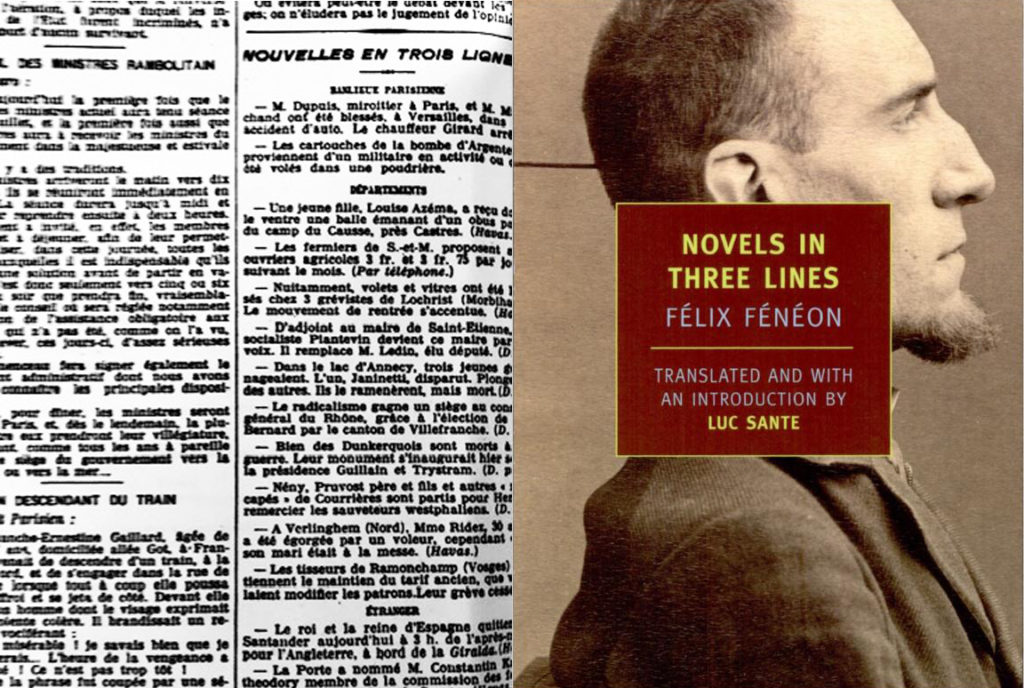

I only bring up these examples to highlight the C-novel’s provenance. But it’s an altogether leaner, meaner fait divers to which the coronavirus novel is more closely related: the Nouvelles en trois lignes (Novels in Three Lines). This marvel of micro-reportage, on events lurid, sordid, grotesque, horrific, tragic, comic, bizarre, absurd, or just mildly quirky, was the work of Félix Fénéon, a brilliant art critic and man of letters who famously sought but failed to achieve anonymity.

Fénéon was a prominent mover and shaker in the intellectual circles of Belle Époque Paris. At various times he served as War Office clerk; art critic, dealer, and gallerist championing the likes of Seurat, Bonnard and Matisse; editor of avant-garde texts by Rimbaud, Gauguin, and Mallarmé; publisher of James Joyce; translator of Jane Austin (Northanger Abbey); and columnist for the influential Parisian daily newspaper, Le Matin.

Last but not least, Fénéon was a dedicated anarchist. In 1896, he was arrested and later tried for collusion in a deadly bomb attack on the Foyot, a restaurant frequented by prominent politicians. Testifying in his defense, his friend Mallarmé would state that “for Fénéon, there are no better bombs than his articles.” Fénéon was acquitted because of lack of evidence—although he did acknowledge culpability toward the end of his life. But his best bombs were yet to come. More than a decade later he would succeed, over a six-month stretch in 1906, in planting some one thousand silent (unsigned) but deadly fait divers in his Le Matin columns.

These three-line news items, culled from the local press, regional newspapers, and wire services of the day, still fizz with corrosive wit.

Napoléon Gallieni, a stonecutter, broke his neck falling down the stairs. He may have been pushed. In any case he was taken to the morgue.

Mme Fournier, M. Vouin, M. Septeuil, of Sucy, Tripleval, Septeuil, hanged themselves: neurasthenia, cancer, unemployment.

In the vicinity of Noisy-sur-École, M. Louis Delillieau, 70, dropped dead of sunstroke. Quickly his dog Fido ate his head.

Contrary to Roland Barthes’ elaboration on the fait divers (“There is an assassination. If it’s political, it’s information; if it isn’t, it’s a fait divers”), Fénéon’s three-line Nouvelles (which can be read as News, or Stories, or even, at a pinch, as Novels) were far from apolitical. Fénéon after all was an avowed anarchist, and subversion lurks in the selection and distillation of his snapshots of the Belle Époque’s underbelly: of petty thefts, crimes of passion, domestic violence, incest, suicides, strikes, labour disputes, random accidents, provincial politics, and so forth. What distinguished Fénéon’s Nouvelles from the run-of-the-mill faits divers of his time was his peculiar sensibility and syntax.

Since childhood Mlle Mélinette, 16, had harvested artificial flowers from the tombs of Saint-Denis. That’s over; she’s in the workhouse.

To get back together with Artémise Riso, of Les Lilas, was the wish of romantic Jean Voul. She remained inflexible. So he knifed her.

Tartayre, of Faillières, Lot, who was arguing with his wife, killed her by throwing at her temple, like a quoit, a plate.

The corpse of the sixtyish Dorlay hung from a tree in Arcueil, with a sign reading, “Too old to work.”

Women suckling their infants argued the workers’ cause to the director of the streetcar lines in Toulon. He was unmoved.

Through a clever game of alternating resignations, the mayor and the town council of Brive have delayed the building of schools.

The reason I keep seeing a template for my coronavirus novel in Fénéon’s faits divers is that for the past four months I have been under lockdown in France, slowly turning up old favourites of French literature. Unsurprisingly, it’s not the big fat Stendhals, Zolas, and Hugos that grab me in these attention-annihilating times, but Félix Fénéon, the miniaturist. Indulging in his Nouvelles, however, has led to an odd reading habit: Nowadays, I am unable to take in any item that catches my eye—in newspapers, news feeds, or news crawls—without boiling it down into a three-line nouvelle of my own. I’m not changing anything substantive, mind you; just altering the order of words here and there; often not changing anything at all. And there it is suddenly, writing itself without my lifting a finger: a coronavirus novel, ready-made.

‘Let us completely block the novel coronavirus,’ is the name of the daily program run by the main television station in North Korea, where no cases of the virus are reported.

Alberto Tito Alejandro, 51, was arrested on an interstate highway after a high-speed chase. Found with his pit bull in the driver’s seat, the man explained that he was teaching the dog to drive.

Defying county “stay-at-home” orders, hundreds of congregants gathered at a Tampa Bay megachurch. ‘Don’t let worry kill you off – let the Church help,’ reads a notice from another church.

In acknowledgment of my close copycatting of Fénéon, however, I had best present a couple of his Nouvelles (below, in italics), followed by my admittedly pale imitations.

Superintendent Chambord decreed that God had no place in the schools. The 11 mayors of Plabennec township, Finistère, demurred.

Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer decreed that staying at home and social distancing were still necessary. 150 militia group members carrying firearms, and people with pro-Trump placards, demurred.

Nitric acid topped off with laudanam was the beverage drunk by M. Paul Malauzet, of Montrouge, when he learned that his wife was deceiving him.

Chloroquine phosphate found in their fish tank cleaning fluid was the poison drunk by a husband and wife who thought it was a coronavirus cure, as touted by President Trump. The husband is dead.

“When the coronavirus has passed,” predicts a New York Times article “we will say, sincerely, perhaps for the first time in our lives, ‘Our long national nightmare is over.’ But this will not be our final use of the phrase. It will be a caption on the Instagram post of someone’s post-quarantine haircut, I promise.”

© Gisèle Guarisco

I can see it now: the nouvelle I’ll be crafting on someone’s post-quarantine haircut—something along the lines, perhaps, of yet another Fénéon classic:

The former mayor of Cherbourg, Gosse, was in the hands of a barber when he cried out and died, although the razor had nothing to do with it.

When the coronavirus has passed. A sobering thought indeed. For when that happens, the rich material for my work-in-progress will have dried up too. Maybe it’s time I started preparing for the end, because the end after all is nigh.

“It’s going to disappear. One day, it’s like a miracle, it will disappear,” President Trump has said. How? “It might be possible to bring light inside the body…through the skin or some other way.”

But as I contemplate the finitude of the novel coronavirus—and with it the finitude of my coronavirus novel—something tells me that time is on my side. Because whatever our Dear Leaders may be saying about the urgency of a swift return to business as usual, Fénéon, I believe, said it best in his summation of a 1906 steelworkers’ strike:

It was believed that work would start up again today at the steelworks in Pamiers. A delusion.

Note: The translations of Félix Fénéon’s Nouvelles en trois lignes quoted here are from Luc Sante’s Novels in Three Lines: Félix Fénéon (New York Review Books Classics, 2007).