THOUGH MOHANDAS GANDHI occupies no formal place as such in histories of nursing in India, it should not come as a surprise to those who have reflected on his long career as perhaps the principal exponent in history of the idea of ahimsa (nonviolence) that he displayed a great affinity for nursing and thought of it as a noble way of rendering service to humankind.

Ahimsa, The Idea of Nonviolence

Gandhi’s capacious understanding of ahimsa has been reduced in common thinking to his articulation of nonviolent resistance to oppression, rendered by the term satyagraha. For Gandhi, nonviolence was a way of being in the world and the unimpeachable law of existence itself. Ahimsa is love itself, a mode of ministering to the soul and nursing the wounds—of others and those which are self-inflicted. Yet Gandhi also had a withering critique of modern medicine and doctors—a critique that does not sit well with the medical profession, though it is notable that this critique did not extend to nursing, even if many of his own thoughts on nursing do not conform to the textbook prescriptions of nursing. He viewed modern medicine as animated by the evil of vivisection and plagued by the profit motive, but his critique of it has other socio-ethical, political, and philosophical dimensions that are far beyond the scope of this paper. For instance, in his 1909 treatise Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, which is increasingly being viewed as the most fundamental expression of his ideas but still lacks the traction and recognition of his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, Gandhi’s critique of the figure of the “doctor” was fundamentally rooted in his deep suspicion of what he calls the “third party.”1 Just as lawyers come between two adversaries and profit only themselves, and just as the British drove a wedge between Hindus and Muslims and set themselves up as a transcendent peace-keeper, so the doctor appeared to Gandhi as someone who distances the patient from his or her own body. He imagines the circumstances under which a visit to a doctor becomes necessary: “I have indulged in vice. I contract a disease, a doctor cures me, the odds are that I shall repeat the vice. Had the doctor not intervened, nature would have done its work, and I would have acquired mastery over myself, would have been freed from vice and would have become happy.”2

Gandhi on Modern Medicine

Happy is not what others have been with Gandhi’s critique of modern medicine and its practitioners, and many have dismissed Hind Swaraj, and certainly his critique of railways, hospitals, and the legal profession, as an ill-informed diatribe. However, his position on modern medicine is easily mischaracterized: in accepting an invitation to inaugurate the opening of a medical college in Delhi in 1921, Gandhi offered his “humble tribute to the spirit of research that fires the modern scientists,” while adding this proviso: “My quarrel is not against that spirit. My complaint is against the direction that the spirit has taken. It has chiefly concerned itself with the exploration of laws and methods conducing to the merely material advancement of its clientele.”3 As he told a German visitor who met with him in 1937, he did “not despise all medical treatment. I know we can learn a lot from the West about safe maternity and the care of infants.”4 If, then, his outlook on medicine still remains unacceptable to many, on the question of nursing, however, he adopted views that may be rather more agreeable and even admirable to most people, most particularly at this time of the coronavirus pandemic when health care practitioners are being celebrated the world over as “front line” workers who have put their lives at risk. He might have thought, incidentally, that the effortless ease with which we have all fallen into speaking of the “front line” suggests the extent to which we have unthinkingly absorbed the vocabulary of war into our thinking, even if he would have understood the spirit in which we have all been called to recognize and applaud the altruistic behavior of those, particularly nurses, who have become part of the corps of “essential” workers. Indeed, it is not too much to say, as shall become apparent in due course, that Gandhi thought of nurses not doctors as “essential,” and in this respect seems to be characteristically contrarian in his thinking.

Nursing and Family

In the matter of nursing, as in many other domains, Gandhi was essentially self-taught. His father had taken ill, suffering from a fistula and confined to the bed, when Gandhi was sixteen years old. “I had the duties of a nurse,” Gandhi recalled many years later in his autobiography, “which mainly consisted in dressing the wound, giving my father his medicine, and compounding drugs whenever they had to be made up at home.” Every night, Gandhi massaged his father’s legs: “I loved to do this service. I do not remember ever having neglected it.” But then came what Gandhi himself called the “dreadful night”: overtaken by the carnal urge, Gandhi left his father’s bedside to share the bed with his own wife, Kasturba, to whom he was married when both were thirteen years old. He had been with her for all of five minutes when a knock came on the door: his father had expired.5 In the centenary year of Gandhi’s death, in an influential book called Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (1969), Erik H. Erikson would go on to argue controversially that the incident and Gandhi’s guilt over it exercised an incalculable influence on his life

Whatever the merits of Erikson’s view, Gandhi’s interest in nursing can be traced to this incident. There would be other occasions, far too numerous to enumerate, where Gandhi would find the opportunity to nurture his instinct for nursing within the ambit of the larger extended family. Gandhi found himself in Bombay in 1896, which was then being decimated by bubonic plague, and he chose to spend day and night by the bedside of his brother-in-law, who had taken seriously ill and whose wife, Gandhi’s sister, “was not equal to nursing him.” Gandhi could not save his life; however, as he was to write years later in his autobiography, “my aptitude for nursing gradually developed into a passion, so much so that it often led me to neglect my work, and on occasions I engaged not only my wife but the whole household in such service.”6 In 1918, when India was struck by the so-called Spanish Flu, Gandhi was taken seriously ill: some have thought that he, too, had been afflicted with that malignant influenza, but the doctor declared that he was suffering from nothing more than “a nervous breakdown due to extreme weakness.”7 Though Gandhi survived the epidemic, his nearness to death was brought home to him by the fact that he lost his grandson, Shantilal, as well as his daughter-in-law, Gulab, to the plague.

Indian Ambulance Corps, South Africa

To the extent that scholars have paid any attention whatsoever to Gandhi’s life-long passion for nursing among a wider public, the narrative generally begins with his initiative in setting up an Indian Ambulance Corps, consisting of 1100 volunteers, during the Boer War in South Africa in 1899. We must recall that Gandhi had made South Africa his home and spent twenty years there before returning to India for good in January 1915. The South African years are vitally important, more particularly if we consider that Gandhi had acquired experience of nursing under conditions of a pneumonic plague epidemic which somewhat resonate with the contemporary experience of Covid-19. In 1904, as he details in his book Satyagraha in South Africa (1928), which recounts the struggle waged by Indians in South Africa to oppose racism and gain political recognition, Gandhi was settled in the Johannesburg area where he had established a law practice. Early that year, he was to write, “a virulent plague broke out among the Indians in Johannesburg. I was fully engaged in nursing the patients . . .”8 He describes his own contribution modestly; however, the Autobiography offers a somewhat more detailed account in two short chapters entitled “The Black Plague-I” and “The Black Plague-II.” Gandhi and his friends took possession of a vacant house by breaking its lock and shifted 23 Indians suffering from the scourge to it, nursing them through the night. The following day, the Municipality made available a vacant if dirty warehouse which they placed at Gandhi’s disposal, leaving the Indians to clean the premises, haul beds into it, and turn it into a “temporary hospital.”9 The Municipality lent the services of a nurse, whose name Gandhi did not recall years later when he wrote his books but who has since been identified as Emily Blake: she became infected and died a few days later, the only nurse to die in that outbreak.

Johannesburg Plague Committee Report

The following year, an official account on the plague appeared under the name of the Johannesburg Plague Committee Report.10 It suggests that neither Ms. Blake, nor any of the Indians (including Gandhi) providing care for the sick, were furnished any protective equipment or masks. The report tacitly recognizes the part played by Gandhi and Dr. William Godfrey, a physician practicing in Johannesburg who had come to the aid of the Indians, in raising the alarm and preventing the plague from taking hold in other parts of the city. “Here, the value of isolating infected persons was immediately appreciated by Dr. Godfrey and Mahatma Gandhi,” says a recent scholarly study of the plague commission’s report, one of the very few that has ever been undertaken, “and progress was made before municipal authorities first realized that the epidemic was fully under way.”11

Still another research essay is yet more pronounced in underscoring Gandhi’s capacious understanding of the circumstances that had no small part in precipitating the plague among indentured Indian workers, whose health in the best of conditions was feeble, and the role he played in bringing the epidemic under control. Delving into previously unexplored correspondence, the author, Tim Capon, notes that since early February 1904 Gandhi had sought to bring to the attention of Dr. Porter, Medical Officer for Health for Johannesburg, the extremely unsanitary conditions under which the Indians lived and the Municipality’s gross negligence in safeguarding their health. Writing to him on February 11, Gandhi described “the shocking state of the Indian location”: “rooms appear to be overcrowded beyond description” and the sanitary services had deteriorated. “From what I believe,” noted Gandhi rather ominously, “I believe the mortality in the location has increased considerably, and it seems to me that, if the present state of things continues, [an] outbreak of some epidemic disease is merely a question of time.” Capon goes so far as to say that “Gandhi helped save not just the Indian community, but also the city itself.”12

Zulu Rebellion and the Natal Volunteer Ambulance Corps

Significant as Gandhi’s interventions appear to have been to stem the rise of the plague in Johannesburg in 1904, his volunteer work during the Zulu Rebellion is still more remarkable for what it reveals about the ethics of Gandhi’s nursing. It is necessary first to revisit his work on the battlefield in 1899 during the Boer War to which I have adverted briefly: though there is an account of this in Gandhi’s own writings, the apparent anomaly of him appearing as a nurse in aid of the British is also explored in what is possibly the most exhaustive history of the Boer War, by the British historian Thomas Pakenham. “Ahead of the field hospitals marched a strange procession,” he writes, “two thousand volunteer stretcher-bearers, who were also political symbols. . . . About eight hundred were members of Natal’s Indian community, led by a twenty-eight-year- old barrister . . . Gandhi had announced in Durban that the Indian community wished to give active expression to their loyalty to the Empire; unable to fight, they would serve as stretcher-bearers. Years later, men might wonder why Mahatma Gandhi, the anti-imperialist and the arch-pacifist, had served as a non-combatant in an imperial war. At the time, it seemed natural enough to the British. Here was one of the ‘subject peoples’ showing the solidarity of the coloured races in the ‘white man’s war.’”13 The work is described by Gandhi himself in his autobiography, though he barely gives it two lines. At a critical moment, despite assurances that the Ambulance Corps would not be required to serve “within the firing line,” Gandhi and the 1100 Indians, 800 of whom were still indentured, were asked if they would be willing to take the risk of removing the wounded from the line of fire. They accepted the risk without hesitation: “During those these days we had to march from twenty to twenty-five miles a day, bearing the wounded on stretchers.” Remarkably, Gandhi rendered his assistance to the British though his own sympathies were with the Boer: as he explained in the autobiography, “I felt that, if I demanded rights as a British citizen, it was also my duty, as such, to participate in the defence of the British Empire.”14

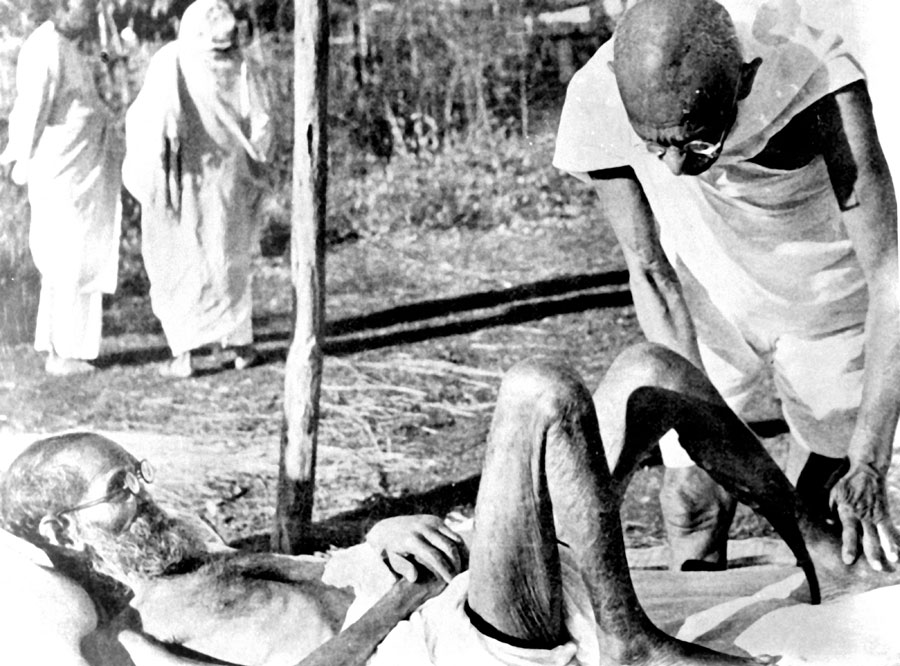

Less than ten years later, Gandhi again found himself raising the Natal Volunteer Ambulance Corps, occasioned by what is known as the Zulu Rebellion. The year, 1906, is recognized by scholars as a pivotal, and doubtless a transformative, moment in his life: he took a vow of celibacy and abjured all sexual relations, even with his wife, for the rest of his life—and this on the grounds that he had come to the conviction that “procreation and the consequent care of children were inconsistent with public service.”15 It is not possible at this juncture to delve into the intricacies of this decision, except to say that, oddly enough, the many scholars who have probed the subject of Gandhi’s views on sexuality have not considered the manner in which the vow came to fruition when he was nursing the wounded Zulus. Two decades ago, in a lengthy paper on the politics of Gandhi’s sexuality, I suggested, contrary to the (still) dominant view that Gandhi’s outlook was characterized by an unhealthy and even repulsive form of sexual puritanism, that it is critical to distinguish between his repudiation of the sexual act but his love of intimacy and sexuality.16 When he took the vow of celibacy, Gandhi did not thereby abjure touch, nor proximity to the bodies of others: both, I would argue, entirely central to his conception of nursing. Let us hear what he has to say: “. . . I was delighted, on reaching headquarters, to hear that our main work was to be the nursing of the wounded Zulus. The Medical Officer in charge welcomed us. He said the white people were not willing nurses for the wounded Zulus, that their wounds were festering, and that he was at his wits’ end. He hailed our arrival as a godsend for these innocent people, and he equipped us with bandages, disinfectants, etc., and took us to the improvised hospital. The Zulus were delighted to see us.”17

The “festering” wounds of which he speaks were a consequence of the floggings by which the Zulus were brow-beaten into submission. These floggings “had caused severe sores” which had been left unattended: their protocols of war—more precisely “the color line” of which W. E. B. Du Bois had spoken three years ago in The Souls of Black Folk—prevented the British from tending to the wounded Zulus, and as we have seen Gandhi remarks that “white people were not willing nurses for the wounded Zulus.” So Gandhi, who had been appointed Sergeant Major of the Corps, commanded a number of men who assisted in tending to the wounded Zulus. Here he resumes his narrative: “The white soldiers used to peep through the railings that separated us from them and tried to dissuade us from attending to the wounds. And as we would not heed them, they became enraged and poured unspeakable abuse on the Zulus.” White people were unwilling to nurse the Zulus, but their voyeurism as they “peep” through the railings while the Indians attended to the wounded men is glaring. Sight has been privileged among the senses, at least in the Western tradition, but Gandhi’s conduct points to the phenomenological importance of touch in his worldview. What is equally inescapable is the magnanimous ethics of hospitality behind the nursing of the Zulus: though Gandhi craved to be accepted as a subject of the British Empire, he plunges headlong into nursing the Empire’s enemies.

Gandhi Today

So what might Gandhi have thought, then, of the present pandemic, the jeopardy in which the livelihood of hundreds of millions of people around the world has been placed, the enormous toll it has taken of human lives, and even, considering his own stated “passion” for nursing, of the advice of scientists and doctors that each one of us should practice “social distancing”? He was very much his own doctor, and a theorist of a biopolitics which placed the responsibility of well-being both upon each individual and the state. He knew enough about public health, and the importance of sanitation, to discern that the advance of the plague in Johannesburg was imminent, and he was sharply critical of the local authorities, having pointed out in a “Letter to the Johannesburg Press” on April 4, 1904 that “but for the criminal neglect of the Johannesburg Municipality, the outbreak would never have occurred”—a statement that he stood by months later, as is revealed in a letter he addressed to the Indian Member of Parliament, Dadabhai Naoroji, on October 31.18 It cannot be doubted that the words, “criminal neglect,” would have formed part of Gandhi’s indictment of how the coronavirus pandemic has been managed by the United States government, but he would also have been critical of the reckless disregard for the lives of others manifested in the behavior of those who are unable to look beyond their own wants, comforts, and drives.

Gandhi held to the view that there are laws of compensation at work in this universe, however opaque they may be to us, and I suspect that, to take one illustration, the comparatively clean air in the wake of the shuttering of the world economy would have been construed by him as a sign to human beings that we should be mindful of the devastation we have wrought upon the earth. But Gandhi was not one to only philosophize: it is impossible to imagine him not present on the scene, tending to the sick and comforting members of their families. Yet, though his compassion was boundless, Gandhi was also tough as nails, and I suspect that he would have punished himself to the hilt in working around the clock, organizing relief workers and cajoling people not to rely on government handouts but to make themselves useful and apply their ingenuity. Gandhi did not require a pandemic to discover, as is true of many of us, that many of those who are among the lowest paid workers are in fact the most “essential.” His relentless critique of industrial modernity has led many people into believing that Gandhi was opposed to science, but that is far from being the case: he was a scientist in his own fashion, ceaselessly testing the truth of every proposition, but, more critically, he was opposed to scientism.

While he would have respected scientific advice, I think it can safely be said that Gandhi would have also said that we cannot leave our understanding of the pandemic and its social, political, and philosophical implications to the scientists alone, because the pandemonium engendered by the pandemic is ultimately a reflection of the unrest within each of us and within homo sapiens as a whole. Magnificent as the nurses have been in tending to the sick and the diseased, we are all called upon to nurse this planetary earth back to health—something which can only begin with the recognition that, as a species, we are likely less “essential” than we have imagined.

Notes

[1] M. K. Gandhi, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House, 1939 [1909], 52-54. Chapter 12 is called “The Condition of India: Doctors.” The edition that is most widely cited by scholars is Hind Swaraj and Other Writings, ed. Anthony J. Parel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). Chapter X, “The Condition of India: The Hindus and the Mahomedans,” references the “third party”: “The fact is that we have become enslaved and, therefore, quarrel and like to have our quarrels decided by a third party.”

[2] Ibid., 53; Parel ed., 63.

[3] M. K. Gandhi, “Speech at Opening of Tibbia College,” 13 February 1921, in The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi [hereafter CWMG], 100 volumes (New Delhi: Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Publications Division), Vol. 19, 356-58; the quote is on p. 358. The entire set is available at https://www.gandhiheritageportal.org/the-collected-works-of-mahatma-gandhi.

[4] This is from a conversation between a certain Captain Strunk and Gandhi: see D. G. Tendulkar, Mahatma: Life of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, 8 vols. (new rev. ed., New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Publications Division, 1961), Vol. 4, 166.

[5] M. K. Gandhi, An Autobiography or the Story of My Experiments with Truth, trans. Mahadev Desai (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House, 1940 [1927]: 21-22.

[6] Ibid., 125-26.

[7] Ibid., 333-34. See also Narayan Desai, My Life is My Message, Vol 2: Satyagraha, 1915-1930, trans. Tridip Suhrud (Hyderabad: Orient BlackSwan, 2009): 111-18.

[8] M. K. Gandhi, Satyagraha in South Africa, trans. Valji Govindji Desai (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House, 1950 [1928], 160).

[9] Gandhi, Autobiography, 216; for the fuller account, see 214-17.

[10] Report upon the outbreak of plague on the Witwatersrand: March 18th to July 31st, 1904. Johannesburg: Argus, 1905.

[11] Charles M. Evans, Joseph R. Egan, and Ian Hall, “Pneumonic Plague in Johannesburg, South Africa, 1904,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 24, no. 1 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 2018), 95-102; https://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2401.161817.

[12] Tim Capon, “Plague, Gandhi and the Parliamentary Clerk’s Daughter,” The Heritage Portal, 9 November 2015, accessed 12 June 2020, http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/plague-gandhi-and-parliamentary-clerks-daughter.

[13] Thomas Pakenham, The Boer War (New York: Random House, 1979): 234.

[14] Gandhi, Autobiography, 156.

[15] Ibid., 150.

[16] Vinay Lal, “Nakedness, Nonviolence, and Brahmacharya: Gandhi’s Experiments in Celibate Sexuality,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 9, nos. 1-2 (University of Texas Press, January-April 2000): 105-136.

[17] Gandhi, Autobiography, 232.

[18] Gandhi, CWMG, 4:287.