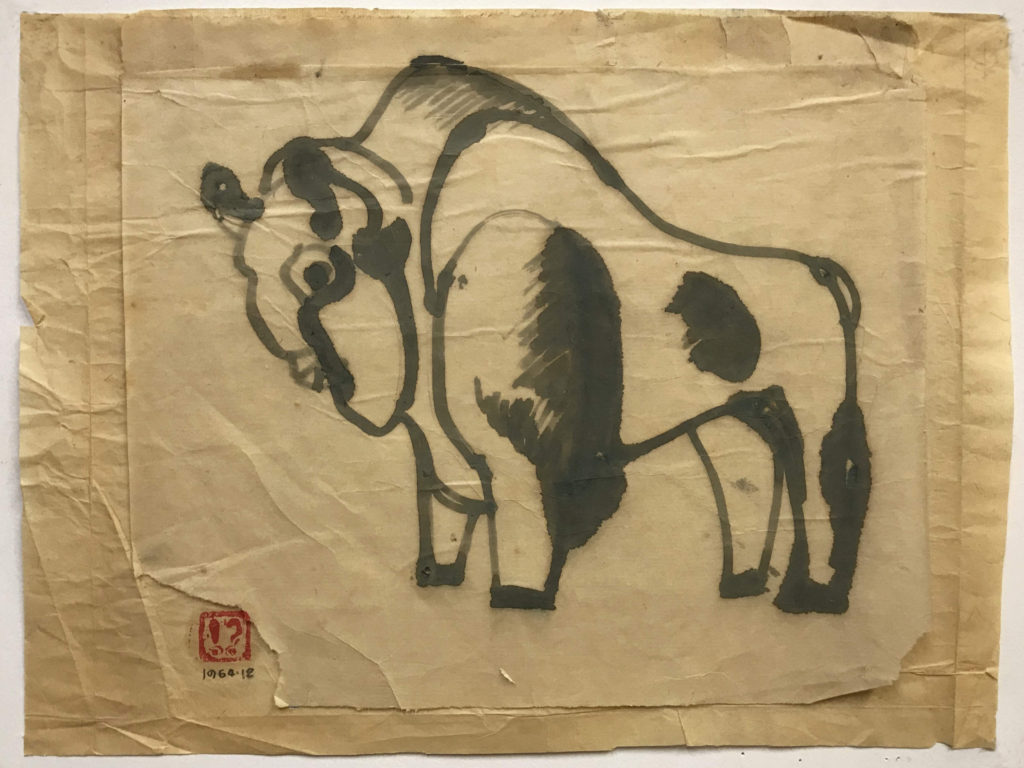

IN 1962, I SKETCHED at the Western Suburbs Zoo in Beijing and saw two North American bison for the first time. Bison are huge in size, brown and black, and move slowly in a space that is not much larger than their bodies. They are incompatible with the zoo, an artificial environment. When sketching, I imagined what it would be like if they lived in the primal wilderness.

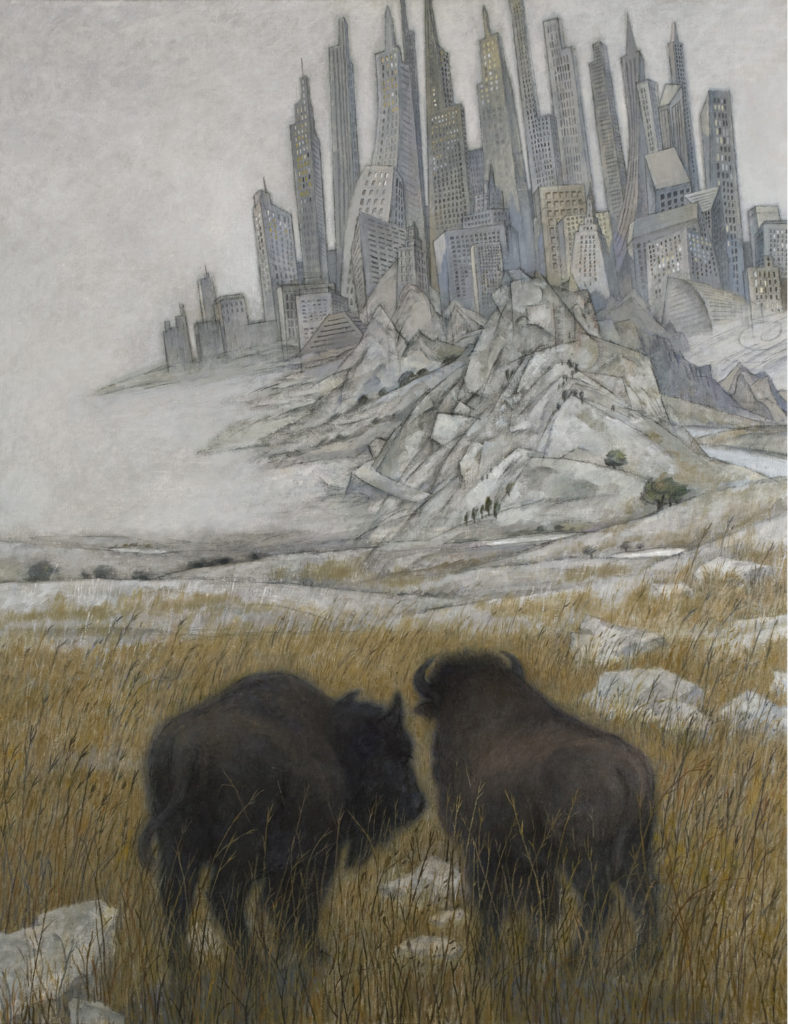

Fifty-six years later in 2018, I saw bison again in the Tallgrass Prairie of Kansas, not just two, but a group of them where there was open space, a lot of grass, and also blue skies and sunlight. However, the bison lived in a conservation area, and wire fences limited their range of movement. The following year I went to Kansas three more times and took thousands of photos of the bison and the grassland. When I took these pictures, I had the same imagination in my head as I did 56 years ago.

I imagined these bison living in the wilderness, but I knew this imagination would always just be an imagination.

I like bison. When I stare at the slow-moving bison on the grassland, I know they are part of the earth, they come from nature, and the wilderness is their hometown.

The North American bison are so powerful that they can run 60 kilometers an hour. They lived with Native Americans on the prairie for tens of thousands of years, but eventually lost to the indiscriminate killing by human latecomers. Only around 300 bison survived in the late 19th century. Although humans have established the conservation area for the bison to breed, because of human greed and the endless over-development of the environment, the wilderness and the landscape upon which humans depend have been irretrievably destroyed.

If bison can dream, they may dream of the wilderness where their ancestors lived.

Today, as I write this during the Covid-19 pandemic, I am not only isolated from people, but like the bison, separated from true wilderness and freedom. Now I can only imagine them through my paintings, drawings, and art.

© Zhang Hongtu

圍繞著北美野牛系列

1962年,在北京西郊動物園畫速寫,第一次見到兩只北美野牛。野牛體型龐大,毛色棕黑,在一個比它們的身軀大不了太多的空間,慢慢地移動著,與動物園這樣的人造環境格格不入。畫速寫的時候,我想象著如果它們生活在原始的曠野會是什麽樣的景象。

56年之後,2018年在北美堪薩斯的高草大草原再次看到了野牛,不是兩只,是一群。它們有很大的的空間,有足夠的青草,還有藍天和陽光,但是,它們生活在一個保護區,有鐵絲的攔網規定了它們的活動範圍。接下來的一年我又去了三次堪薩斯,拍了上千張野牛和草原的照片,拍照時我腦子裏出現的是和56年前同樣的想象,想象這些野牛生活在曠野的景象,但是我知道,這種想象將永遠只是想象。

我喜歡野牛。當我凝視著緩慢的在草原上移動的野牛,我知道它們是大地的一部分,它們來自于自然,曠野是它們的家鄉。

北美野牛力大無比,一小時能跑60公里,它們和北美原住民在大草原上共同生活了上萬年,但是最終不敵後來的人類對它們的濫殺,到19世紀末,整個北美只剩下300多頭野牛。人類雖然爲野牛建立了保護區使之得以繁殖,但是因爲人類的貪婪和爲了滿足自己的欲望而永無休止的對環境的過度開發,使得曠野和人類賴以生存的自然遭到了無法挽回的破壞。

野牛如果會做夢,它們可能每天都夢到祖先們生活的曠野。

今天,當我在Covid-19疫情期間寫這篇短文時,我不僅被與他人隔離,也像野牛一樣,被隔離於真正的荒野和自由,唯一能做的是借助於藝術來想像它他們。

© Zhang Hongtu