“Wherever our memories, story fragments, visual details, and thoughts laid in the finished comics, they will be different, new, and perhaps…revelatory” — M.K. Czerwiec

ON JANUARY, 23, 2020, two days before Chinese New Year, the Chinese central government ordered a total lockdown of Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province, and other cities in the province in an attempt to stem the outbreak of a new coronavirus disease—now known as COVID-19. The lockdown ended on April 7, 2020, lasting seventy-six days. About forty-two thousand medical personnel from different parts of China were mobilized to work at ground zero of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 While numerous creative works have emerged out of the lockdown, two pieces in distinct graphic forms specifically present the experience of medical support teams in Wuhan.

Visual Stories through Comics

Medical Team Diary 《醫療隊日記》 by Dr. Zhou Haibo (周海波) offers an eyewitness account, and One World, One Fight 《世界加油》 produced by Gen Z Group presents a fictionalized narrative of healthcare workers’ efforts in Wuhan.2 Whereas Medical Team Diary manifests an overflow of patriotic sentiments, the main message that One World, One Fight tries to communicate is of global outreach and cooperation. Together, the two works embody practices of graphic medicine in which stories of illness and healthcare work are presented via the visual medium of comics.3

Medical Team Diary

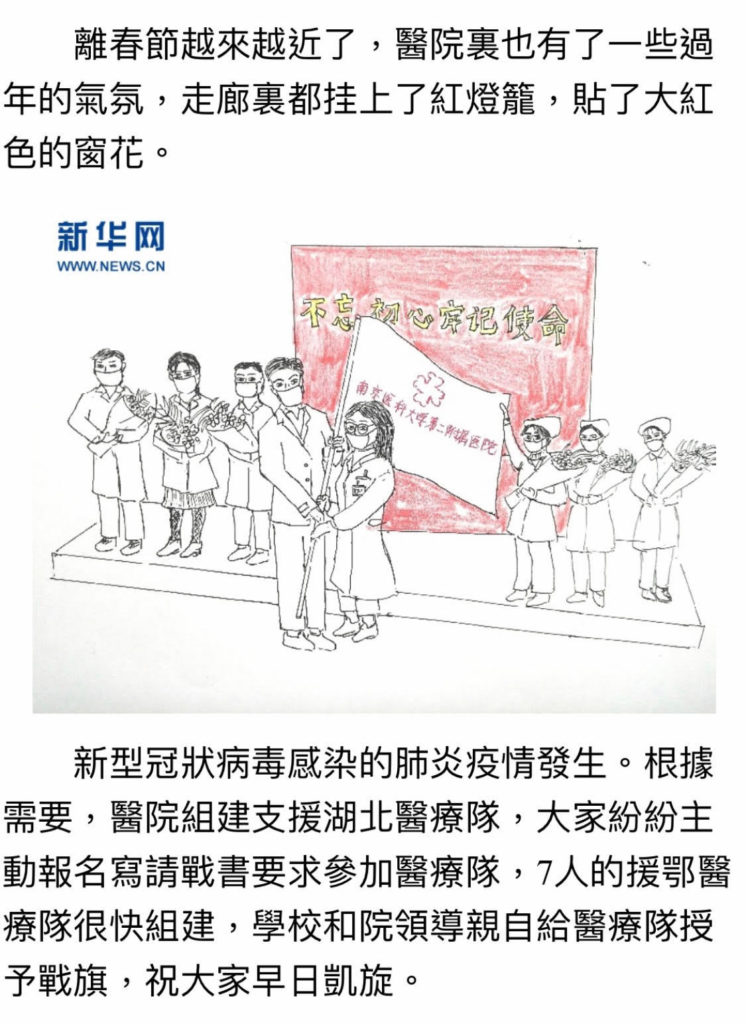

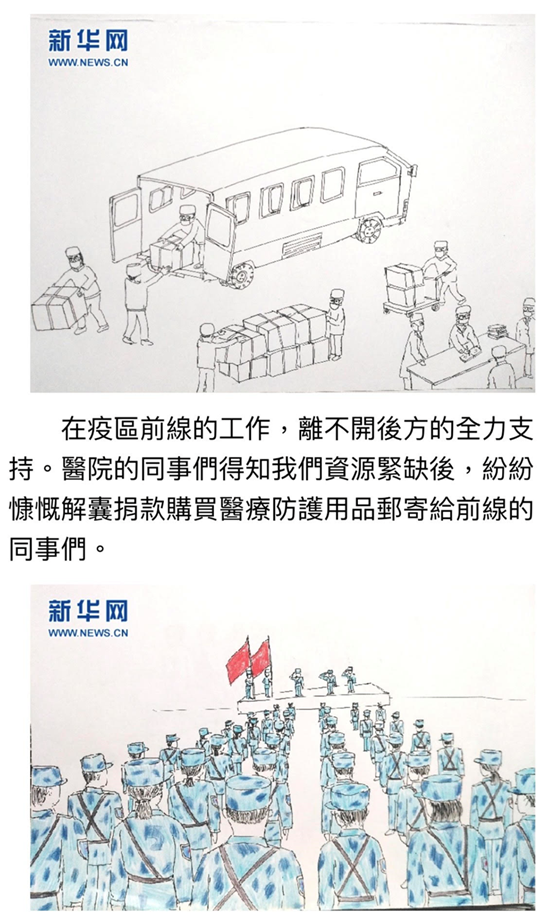

Dr. Zhou’s Medical Team Diary is comprised of fifteen panels of line drawing depicting how Zhou and other volunteers from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University participate in fighting COVID-19 at the frontline. With textual explanation beneath each panel, the sketches, in an amateurish style, present Dr. Zhou’s engagement in the rescue mission at Wuhan. Except for the first two panels, in which the color red is used to suggest the festivity of Chinese New Year, the group of military medical staff in the blue uniforms of People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and China’s national flag in red in the final panel, the rest of the twelve panels are all in black and white to mourn for the victims of the pandemic.

Source: Xinhua News

Zhou admits that he has read extensively journalistic accounts of medical work in Wuhan and wants to capture “memorable moments” in his diary. In addition to Zhou’s personal experience of traveling to Wuhan with the blessings of friends and relatives, and his clinical work with patients, some of the sketches clearly exhibit media influences. As Ian Williams points out, “[t]he author’s iconography will depend on influences from art, personal observation, and consumption of other medically-themed media, articulated in a blend of intentional and unintentional signs. It will also depend on the skill and style of the artist” (118-19). Clearly Zhou has decided to acknowledge the influence of public images of Wuhan’s medical workers in configuring his iconography of COVID-19.

In one panel, we encounter an image of a medical worker sleeping soundly on a lounge chair while wearing a diaper, which echoes the reported shortage of medical supplies in the early days of the lockdown during which many healthcare workers resorted to wearing diapers so that they could make the best use of the personal protective equipment (PPE). In the next panel stand two doctors with their backs to the reader, representing healthcare workers as “heroes in harm’s way” (逆行者) who run towards danger in order to save their country and the people.4 The last panel of the diary shows a salute to the PLA that is strikingly similar to a photograph presenting the gathering of a group army doctors before heading their way to Wuhan on the eve of Chinese New Year.5

Instead of being a personal recollection of the hardship in treating the COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, Zhou’s Medical Team Diary moves beyond the sense of intimate privacy suggested by the diary as a genre to construct and consolidate a collective memory commemorating heroic patriotism. The textual explanations accompanying the fifteen panels present, in no uncertain terms, the determination to triumph over the pandemic, led by strong party and national leadership.

Source: Xinhua News

One World, One Fight

In the post-lockdown period from April to June 2020, the Singapore-based educational media company Gen Z Group published online, One World, One Fight, a five-episode graphic series about the battle against COVID-19 in Wuhan. According to Tiffany Liu, the project is inspired by the United Nations’ GLOBAL CALL TO CREATIVES: An Open Brief, inviting people around the world to respond to the pandemic with creative projects. With medical content adapted from the Handbook of COVID-19 Prevention and Treatment published by the Jack Ma Foundation and the First Affiliated Hospital of the School of Medicine of Zhejiang University, One World, One Fight aims to “raise awareness for COVID-19 prevention and treatment practices adopted by Chinese healthcare workers as case studies for the global community, to avoid any overlapping efforts, and to bridge the gap between professionals and public by using graphic novel as a visual medium in communicating technical terms” (Liu). The series has been translated into fifteen languages to increase its global impact. However, it is through the use of graphic images that the production team hopes to reach beyond national and professional boundaries.

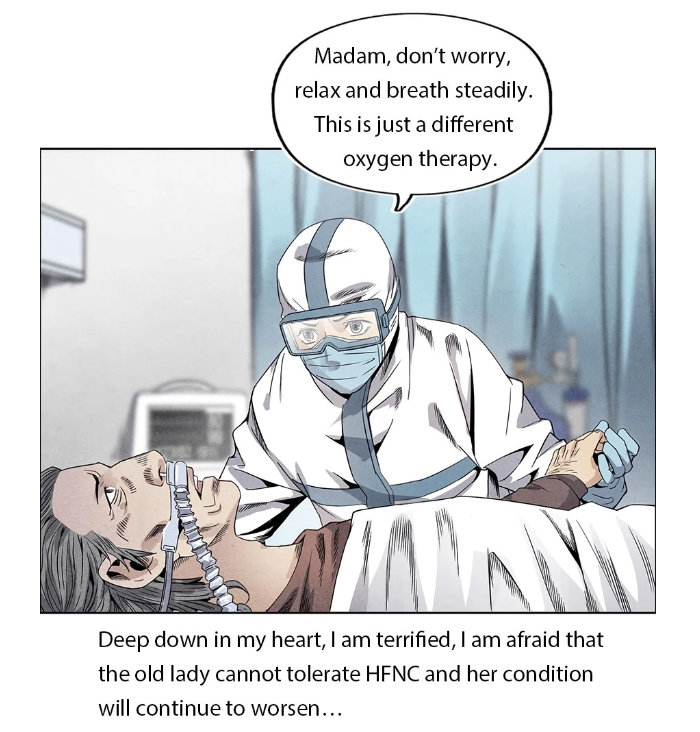

Unlike the amateur, hand-drawn sketches in Zhou’s Medical Team Diary, One World, One Fight is illustrated by the popular contemporary Chinese comics artist, The Revolver. With a similar goal of documenting the struggle against the pandemic in the epicenter by volunteer healthcare workers as in Zhou’s graphic diary, One World, One Fight offers a fictional account of the medical mission witnessed by a 28-year-old volunteer, Wendy Hao (郝靜雯), and interestingly evinces a much stronger sense of intimacy than does Zhou’s diary. We see, for instance, that Wendy’s parents are adamantly opposed to her going to Wuhan, where she received her medical education, to the point that the father threatens to disown her. We see Wendy’s resultant pain and sense of ambivalence. In fact, the graphic novel is emplotted as a Bildungsroman, recording Wendy’s training and development as a medical professional fighting COVID-19.

Alternating between third- and first-person perspectives, the descriptive narratives offer medical knowledge regarding protective measures against infection, some as specific as the donning and taking off of PPE, as well as Wendy’s internal monologues that reveal her fear and anxiety in the face of the unknown virus. Excerpts of the medical Handbook are included at the end of each episode, providing practical information for medical staff. This hybrid combination of medical instruction and fictional representation evidences the significance of graphic medicine in medical education. As Michael J. Green asserts about the usefulness of integrating comics into the medical school curriculum, “[t]hey can tell compelling stories about illness and demonstrate the complexity of medical culture” (82). While facing a novel virus and disease, such as COVID-19, the graphic form can effectively educate healthcare professionals and lay people alike regarding treatment and self-care.

Episode One of the graphic novel opens with a panel showing a high-speed train rushing through heavy rain. In the next panel, a sad and gloomy Wendy is seen doodling on the foggy window of the train. In contrast to the celebratory mood of Zhou’s diary when the medical support team members are on board the train to Wuhan—some are shown filling out applications to become Communist party members— Wendy’s train ride is overshadowed by familial discord. The eerie emptiness at the train station and on the streets of Wuhan, “a metropolitan with 11 million people” (One World, One Fight) during Chinese New Year accentuates Wendy’s uncertainty about her decision, which again differs from the sense of determination in Zhou’s work. Wendy faces another setback when she fails the personal protection assessment upon arriving at Wuhan and is sent to do community health service instead of working on the frontline.

Episode Two shows Wendy trying to promote preventive measures against the coronavirus among uncooperative people in a local community. In the process of working with the citizens of Wuhan, Wendy graduates from feeling frustrated to realizing the importance of preventing the spread of the virus. Accompanying an infected elderly lady to the hospital, Wendy is finally recruited to treat COVID-19 patients and moves into another phase of her “education.” For the rest of the graphic novel, Wendy is seen mostly in PPE, tending to the elderly lady—from collecting a respiratory tract specimen, to finding ways to help her muster courage to fight for her life, curing her, and sending her home—becomes Wendy’s major task in the graphic narrative.

In addition to illustrating Wendy’s progress in battling the pandemic, which includes wearing adult diapers to save precious medical resources, as is also shown in Zhou’s work, the experience with the elderly lady apparently serves as a case study embodying the process of treating COVID-19 patients. The infection of Dr. Li, Wendy’s mentor, realistically presents the hazard confronting healthcare providers in the face of the unpredictable disease. The turning point comes in Episode Four when the recovering Dr. Li is seen practicing Tai Chi in the ward to keep his body fit, which considerably inspires the disheartened medical staff, and when Wendy successfully revives the comatose elderly lady.

Source: Gen Z Group, www.genzgroup.org/post/english_oneworldonefight

The graphic novel ends with the arrival of the cherry blossom season—cherry blossoms being an important emblem of Wuhan—and the completion of Wendy’s medical education when she finally realizes the meaning and significance of the medical profession. The overall rosy tint of the final episode replaces the depressing grey and dark tone of the earlier episodes to convey a sense of optimism and regeneration. Much like Dr. Zhou’s Medical Team Diary, the ending of One World, One Fight is intended to present hope in fighting the virus. The English title of the series, moreover, places special emphasis on the importance of global cooperation in combating COVID-19. As Tiffany Liu asserts, “We are all in this together, and we can’t beat this virus unless we actively share our resources and know-hows.” Sharing, instead of pointing fingers and playing the blaming game, leads the way to final victory in this battle against the viral species.

A Graphic Medicine for Uncertain Times

Theorizing the importance of graphic narratives for healthcare providers, M. K. Czerwiec claims that “drawing a comic—which requires things we each already possess: words, a visual language, a writing implement, and a blank piece of paper—has enormous potential when used in the medical context” (145). Based on her own personal experience as a nurse in a now disbanded AIDS unit and teaching a “Drawing Medicine” seminar to medical students, Czerwiec believes in the transformative power of visualization: “Wherever our memories, story fragments, visual details, and thoughts laid in the finished comics, they will be different, new, and perhaps…revelatory” (152). The very fact that both Dr. Zhou and Gen Z Group have chosen the visual medium of comics for the important task of memorializing the pandemic underlines the importance of graphic medicine, especially in difficult times of uncertainty and unpredictable biological entities such as COVID-19.

Notes

[1] The number comes from China’s official news agency, Xinhua Net (新華網). Please see http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-03/17/c_138888538.htm.

[2] Please go to Xinhua Net to read Medical Team Diary (http://big5.xinhuanet.com/gate/big5/www.js.xinhuanet.com/2020-02/07/c_1125544010.htm), and Gen Z Group to read One World, One Fight (https://www.genzgroup.org/blog).

[3]“Graphic medicine” is a term coined by Ian Williams when he created the website Graphic Medicine to post notes about works utilizing graphic forms to represent the experience of healthcare and illness (Williams 116).

[4] The term “heroes in harm’s way” comes from a talk of Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, at the 56th Munich Security Council on 15 February 2020. See China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1746165.shtml.

[5] Please see https://kknews.cc/zh-tw/military/4bga8a2.html.

Works Cited

- M. K. Czerwiec, et al., Graphic Medicine Manifesto (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2015).

- M. K. Czerwiec, “The Crayon Revolution,” M. K. Czerwiec, et. al., 143-63.

- Michael J. Green, “Graphic Storytelling and Medical Narrative: The Use of Comics in Medical Education,” M. K. Czerwiec, et. al., 67-86.

- Tiffany Liu, “Spotlight: One World, One Fight,” Graphic Medicine, 20 May 2020, accessed on 22 May 2020, https://www.graphicmedicine.org/spotlight-one-world-one-fight/.

- “One World, One Fight,” Gen Z Group, accessed on 22 May 2020, https://www.genzgroup.org/blog.

- Ian Williams, “Comics and the Iconography of Illness,” M. K. Czerwiec, et. al., 115-42.

- Haibo Zhou, “Medical Team Diary,” Xinhua Net, 7 February 2020, accessed on 8 February 2020, http://big5.xinhuanet.com/gate/big5/www.js.xinhuanet.com/2020-02/07/c_1125544010.htm.